Section 9. Safeguards for children and applicants with special needs

EU legislation contains provisions to address the special needs of applicants who may be considered particularly vulnerable in the asylum system. These provisions ensure that vulnerable applicants receive adequate support to benefit from their rights and comply with the obligations which are defined under CEAS so that they can be on an equal footing with other applicants.

The concept of vulnerability is present across the legislative pieces under the Pact, obliging authorities in Member States to swiftly identify and follow up on potential special procedural and reception needs. Vulnerability assessments must start as soon as possible and an applicant’s situation is to be monitored throughout the international protection procedure. The assessment is individualised and undertaken by staff who must be qualified, specialised and continuously trained, with the assistance of an interpreter.

The best interests of the child must be the primary consideration of national authorities when applying the Pact instruments. Applicants receive information on their specific rights and obligation as applicants with special needs, which must also be available in a child-friendly manner. A representative is appointed as soon as possible for unaccompanied children for the entire procedure. The representative is a natural person who must be qualified and trained, may be in charge of a maximum number of children and has specific tasks identified under each piece of legislation. As a rule, children are not detained, and when detention would put an applicant’s physical or mental health at serious risk, they should not be detained either.

Prior to their displacement and during their journey, applicants for international protection may be subjected to abuse, exploitation and violence.388 Among them, numerous women, girls and boys have experienced extreme forms of violence, including sexual violence.389 National authorities noted that perpetrators often film these acts and use this to blackmail their victims for further exploitation. Against this background, the successful application of the additional safeguards under the Pact is key, including the measures for swifter identification and fast follow-up for vulnerabilities and special procedural and reception needs.390

National authorities highlighted their commitment to meet these new requirements, but they also expressed that this area was one of the most challenging. Civil society organisations across several EU+ countries also assessed that one of the major issues was the lack of sufficient resources for swift identification, age assessments, legal guardians and follow-up services, such as mental healthcare.391 To support the process, the EUAA has developed a Guidance on Vulnerability in Asylum and Reception.392

As the pressure continued on asylum and reception authorities in 2024 (see Sections 4 and 5), there was reduced capacity to provide adequate follow-up for physical and mental health issues, including trauma.393 For example in Ireland, resources dedicated to vulnerability assessments were redirected to vulnerability triage for all single men whom the International Protection Accommodation Services could not accommodate. The vulnerability assessment programme for all families recommenced in November 2024 with further plans to extend to single women and couples in 2025. The vulnerability triage remains operational due to the ongoing shortage of accommodation for single men. The distribution procedure resumed in July 2024 in Berlin, Germany, after it was suspended due to the high arrival of unaccompanied children in 2022 and 2023.

The EU’s revised Anti-Trafficking Directive was adopted in May 2024, expanding its scope to include forced marriage, illegal adoption and the exploitation of surrogacy as crimes. The directive also obliges Member States to implement more rigorous tools to investigate and prosecute new forms of exploitation and provide a higher level of support services to victims of trafficking. Several EU+ countries drafted or updated their national anti-trafficking action plans based on the new rules. For the practical implementation of the plans, initiatives varied from staff training to the development of multilingual information tools, which were typically implemented in cooperation with civil society organisations and local authorities. Stakeholders observed with concern the rapidly-evolving and growing use of new technologies for trafficking and exploitation and underlined the need for harmonised data collection to better understand the phenomenon and prepare more adequate counter-measures.394

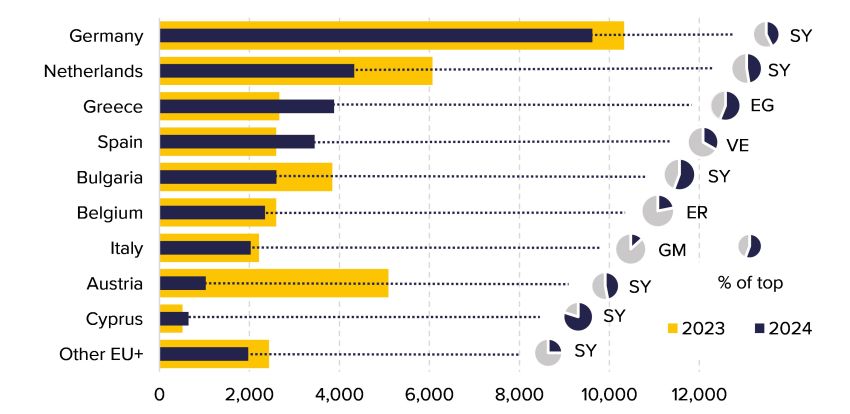

In 2024, 32,000 asylum applications were lodged by self-claimed unaccompanied minors, approximately 16% less than in 2023. Although experiencing a slight decline, Germany continued to be the top receiving country accounting for 30% of the total, with 9,600 applications (see Figure 18). Among the top receiving countries, Austria had the most significant drop in applications by unaccompanied minors, with 1,000 applications representing an 80% decrease.

In contrast, Greece received an unprecedented number of applications by unaccompanied minors. The 46% increase (3,900 applications) was primarily due to many more Egyptians. Although at lower levels, applications by unaccompanied minors increased by over a quarter in Cyprus (650 to the second-highest number on record.

Figure 18. Top EU+ countries receiving applications by self-claimed unaccompanied minors, 2024 compared to 2023 and share of applications lodged by the main citizenship of unaccompanied minors, 2024

Source: EUAA EPS data as of 3 February 2025

Almost one-half of unaccompanied minor applicants in the EU+ were either Syrians (10,000 applications) or Afghans (4,500). While both decreased, applications by Afghans dropped sharply to their lowest level since 2019. In contrast, record numbers of applications were lodged by unaccompanied minors from Egypt (2,900 applications, almost all of them in Greece and Bulgaria), Ukraine and Peru. In addition, applications by unaccompanied minors from Guinea, The Gambia, Mali and Senegal spiked to the highest levels since at least 2018.

The majority of initiatives by national authorities in 2024 focused on supporting minors, especially unaccompanied children. Greece continued to host a large number of unaccompanied children, many of them in precarious living conditions or homeless and trapped in addiction and crime.395 To assist, the EU provided essential funding for the National Emergency Response Mechanism (NERM), which was launched by Greek authorities in 2021. Since its creation, the mechanism has contributed to the early detection and safe accommodation of almost 5,000 migrant children.396

Another significant change took place in Slovenia, where a new regulation entered into force on measures to ensure adequate accommodation, care and treatment for unaccompanied minors.397 A new regulation in Italy revised the template for the entry interview that reception facility operators conduct with unaccompanied children, aiming to harmonise approaches in identification and follow-up.398 Improvements in the care for unaccompanied children were prompted by recommendations of the Commissioner for Children’s Rights and the Commissioner for Human Rights in Poland399 and legislative amendments,400 while Croatian authorities embarked on the harmonisation of the protocol for unaccompanied minors in light of the Pact. The Norwegian UDI and UNE prepared amendments to their procedures based on the findings of a study that analysed their practices in the assessment of the best interests of the child.401 The study found that at times considerations of immigration regulations overshadowed the consideration of the best interests of the child. The Austrian Federal Administrative Court updated its guidance for judges on the best interests of the child in asylum and immigration procedures.402

Practices in age assessments were finetuned in several countries, following developments in medical and legal standards, for example in Ireland, Malta403 and Sweden. Civil society organisations noted that this area still needed improvement in several EU+ countries and highlighted the need for a multidisciplinary approach going beyond medical assessments.404

Several AMIF projects were running in 2024 to better support minors. For example, one project aimed to establish systematic sport activities for young adults in COA facilities405 in the Netherlands, while another focused on the child-friendliness of reception centres in Belgium.406

A worrying phenomenon continued with the detention of children across EU+ countries, as documented in court judgments (including at the level of the ECtHR),407 and reports from international and civil society organisations.408 The recast RCD 2024 now states that minors cannot be detained “as a rule”, and for example, Belgium and France amended legislation in 2024 to spell this out.409

Another area of focus was the protection of female applicants, marked by several CJEU landmark judgments, C-621/21,410 C-646/21411 and C‑608/22 and C‑609/22.412 With these judgments, the court established that:

- gender is an innate characteristic fulfilling the first criteria for membership of a social group and women as a whole may qualify for international protection, as well as groups of women who share an additional common characteristic;

- women, including minors, who identify with the fundamental value of equality between women and men during their stay in a Member State may belong to particular social group which can face persecution in their country of origin;

- an individual risk assessment is not necessary when discriminatory state measures amount to acts of persecution, and that refugee protection may be granted after establishing only gender and nationality.413

Court rulings in the national context highlighted that asylum authorities must provide an adequate investigation and reasoning, using reliable and up-to date COI to assess the situation in the applicants’ country and area of origin, with a particular focus on gender-based violence and harm. They also overturned decisions by asylum authorities for failure to assess the need for special procedural guarantees for vulnerable women who were victims of gender-based violence.414

Two national authorities reported important changes that aimed to strengthen safeguards for victims of sexual violence and female genital mutilation/ cutting (FGM/C). In France, a new decree was adopted on the medical examination of FGM/C cases415 and a new webpage was launched for healthcare professionals with a section devoted to the issuance of medical certificates related to FGM/C cases.416 The Belgian CGRS adopted new internal guidelines on the handling of applications for international protection based on the ground of sexual violence. The policy on follow-up to FGM/C cases was also changed after serious considerations: girls who were granted international protection for fear of FGM/C must undergo a medical check every 3 years, instead of every year. The authority made this change noting the difficulty for some girls to participate in the yearly checks and the psychological impact of the checks. These measures were accompanied by civil society initiatives, for example the EU-funded END FGM E-Campus project which is implemented by a group of universities and civil society organisations.417

Amid the scarcity of information available on applicants with disabilities, the EUAA published two comprehensive reports which provide an overview of policies, practices, legislation and diverse initiatives for asylum applicants and displaced Ukrainians with temporary protection. The reports also describe the challenges in EU+ countries.418 Throughout 2024, only a few developments followed at the national level. For example, Belgium continued with a project to strengthen the approach of the CGRS on the participation of applicants with physical or mental disabilities in the asylum procedure and the substantive assessment of their cases.419 At the same time, country reports published by the Commission for the Rights of Persons with Disability (CRPD) highlighted the difficulties applicants with disabilities faced in accessing support services.420 For example, the timely access to psychological support starting from initial reception remained a concern.421

A request for a preliminary ruling was pending with the CJEU on the possibility of courts to directly order the national authority to refer an applicant for a medical examination as part of the right to an effective medical remedy.422ECRE argued for strategic litigation to clarify the scope of guarantees for applicants with disabilities, based on the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and the CRPD.423

The daily life of applicants with diverse sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and sex characteristics (SOGIESC) remained marked with different challenges.424 According to a FRA report, while reporting of incidents was low in general, asylum applicants with SOGIESC reported more frequently than their non-applicant peers about discrimination and hate-motivated violence.425 In order to support EU+ countries in the correct and effective implementation of the relevant EU rules, the EUAA developed a guide on SOGIESC in asylum, covering aspects related to reception, the examination procedure and cross-cutting elements of these two fields, accompanied by an information note on SOGIESC-related concepts and terms.426

Court decisions in 2024 indicated several gaps in the adequate assessment of SOGIESC claims,427 and research efforts continued to address systemic stereotypes that lead to incorrect decisions.428 Among national developments, only the Danish Immigration Service highlighted a new guide which was launched to raise awareness among reception staff on the specific needs and support measures for applicants with diverse SOGIESC.429

- 388

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2024, July 24). Missione congiunta UNHCR-UNICEF a Lampedusa: indispensabile rafforzare l’accoglienza e il supporto per minorenni e persone con vulnerabilità specifiche [UNHCR-UNICEF Joint Mission to Lampedusa: it is essential to strengthen reception and support for minors and people with specific vulnerabilities].

- 389

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2024, July 24). Missione congiunta UNHCR-UNICEF a Lampedusa: indispensabile rafforzare l’accoglienza e il supporto per minorenni e persone con vulnerabilità specifiche [UNHCR-UNICEF Joint Mission to Lampedusa: it is essential to strengthen reception and support for minors and people with specific vulnerabilities]. FENIX Humanitarian Legal Aid. (2024, March 8). A gendered gaze on migration: Report on sexual and gender-based violence in the context of the Greek asylum policy on Lesvos.

- 390

European Commission. (2024, June 12). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Common Implementation Plan for the Pact on Migration and Asylum. COM(2024) 251 final.

- 391

Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid | Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugiado. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025. Network for Children's Rights | Δίκτυο για τα Δικαιώματα του Παιδιού. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025. Refugee Council of Lower Saxony | Flüchtlingsrat Niedersachsen e.V. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025. Jesuit Refugee Service Europe. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025. Safe Passage International. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025. Nidos Foundation | Stichting Nidos. (2024). Input to the Asylum report 2025. Irish Refugee Council. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025. Greek Council for Refugees | Ελληνικό Συμβούλιο για τους Πρόσφυγες, & Save the Children. (October 2024). "It does not feel like real life": children’s everyday life in Greek refugee camps.

- 392

European Union Agency for Asylum. (May 2024). Guidance on vulnerability in asylum and reception: Operational standards and indicators.

- 393

Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid | Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugiado. (2024, November 20). CEAR alerta sobre la situación de desprotección de niños y niñas que buscan refugio [CEAR warns about the lack of protection for children seeking refuge]. Spanish Ombudsperson | Defensor Del Pueblo. (2024, July 30). Situación de los menores extranjeros no acompañados en Canarias [Situation of unaccompanied foreign minors in the Canary Islands]. Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration | Associazione per gli Studi Giuridici sull'Immigrazione. (2024, January 4). Il Tribunale per i Minorenni di Catania interviene a tutela dei minori collocati nella tensostruttura di Rosolini [The Juvenile Court of Catania intervenes to protect the minors placed in the Rosolini temporary structure]. United Nations, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. (2024, May 17). Concluding observations on the seventh periodic report of Estonia. United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. (2024, April 29). Concluding observations on the combined second and third periodic reports of Sweden. CRPD/C/SWE/CO/2-3. United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. (2024, September 30). Concluding observations on the combined second and third periodic reports of Belgium. CRPD/C/BEL/CO/2-3. United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. (2024, October 8). Concluding observations on the combined second and third periodic reports of Denmark. CRPD/C/DNK/CO/2-3. United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. (2024, June 18). Concluding observations on the combined fifth to seventh periodic reports of Estonia. CRC/C/EST/CO/5-7. United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. (2024, March 7). Concluding observations on the combined fifth and sixth periodic reports of Lithuania.

- 394

European Union Agency for Asylum. (2024, August 19). Victims of human trafficking in asylum and reception. Situational Update No 21.

- 395

Save the Children. (2024, December 11). Child migrant and refugee arrivals in Greece double in 2024, as children report alarming camp conditions. European Federation of National Organisations working with the Homeless. (2024). Children facing homelessness and poor housing: A European reality.

- 396

European Commission. (2024, April 19). An EU-backed project keeps thousands of migrant children safe and off the streets.

- 397

Uredba o načinu zagotavljanja ustrezne nastanitve, oskrbe in obravnave mladoletnikov brez spremstva [Regulation on the method of ensuring appropriate accommodation, care and treatment of unaccompanied minors], 12 October 2023.

- 398

Ministry of Labor and Social Policies | Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali. (2024, July 10). Minori stranieri non accompagnati, così il colloquio all'ingresso in accoglienza [Unaccompanied foreign minors, so the interview at the entrance to reception].

- 399

Ombudsman | Rzecznik Praw Obywatelskich. (2025, January 30). Problemy cudzoziemskich dzieci bez opieki, które przekraczają granicę Polski z Białorusią. Pismo RPO i RPD do premiera. Odpowiedź MSWiA [Problems of unaccompanied foreign children crossing the Polish border with Belarus. Letter from the Commissioner for Human Rights and the Commissioner for Children to the Prime Minister. Response from the Ministry of the Interior and Administration].

- 400

Office for Foreigners | Urząd do Spraw Cudzoziemców. (2024, December 16). Polityka ochrony dzieci przed krzywdzeniem w ośrodkach dla cudzoziemców prowadzonych przez UdSC [Policy of protecting children from harm in centers for foreigners run by the Office for Foreigners].

- 401

KPMG. (2024). Summary and recommendations - Immigration authorities’ assessments of the best interests of the child in asylum cases.

- 402

Federal Administrative Court I Bundesverwaltungsgericht. (2024, May 28). Das Kindeswohl im Asyl- und Fremdenrecht – ein Leitfaden [The best interests of the child in asylum and immigration law – a guide].

- 403

Act No 104 of 2024 - Procedural Standards for Granting and Withdrawing International Protection (Amendment) Regulations, 2024, 26 April 2024.

- 404

I want to help refugees | Gribu palīdzēt bēgļiem. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025. Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights | Helsińska Fundacja Praw Człowieka. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025. Swiss Refugee Council | Schweizerische Flüchtlingshilfe | Organisation suisse d’aide aux réfugiés. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025.

- 405

Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers | Centraal Orgaan opvang asielzoekers. (February 2025). AMIF-project ‘Activering’ [AMIF project "Activation".

- 406

Federal agency for the reception of asylum seekers | L’Agence fédérale pour l’accueil des demandeurs d’asile | Federaal agentschap voor de opvang van asielzoekers. (2024, November 11). Des centres mieux adaptés aux enfants [Centers better adapted to children]. Fournier, K., van Acker, K., & Geldof, D. (2024). A quel point ton centre est-il adapté aux enfants? [How child-friendly is your centre?]. Odisee University of Applied Sciences, Knowledge Centre for Family Sciences | Odisee Hogeschool, Kenniscentrum Gezinswetenschappen.

- 407

EUAA Case Law Database. Detention/Alternatives to Detention.

- 408

aditus foundation (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025. Lithuanian Red Cross Society | Lietuvos Raudonojo Kryziaus. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025. Save the Children. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025. Jesuit Refugee Service Europe. (2024). Detention under the spotlight: Germany. Issue no. 8. Polish Migration Forum Foundation | Fundacja Polskie Forum Migracyjne, & Save the Children. (May 2024). Everyone Around is Suffering. Save the Children. (2024, December 17). Nascosti in Piena Vista: cosa accade ai minori stranieri soli a 18 anni [Hidden in Plain Sight: What Happens to Unaccompanied Foreign Minors at 18].

- 409

Loi n° 2024-42 du 26 janvier 2024 pour contrôler l'immigration, améliorer l'intégration (1) [Law No 2024-42 of 26 January 2024 for controlling immigration and improving integration (1)], 26 January 2024. Loi du 12 mai 2024 modifiant la loi du 15 décembre 1980 sur l'accès au territoire, le séjour, l'établissement et l'éloignement des étrangers et la loi du 12 janvier 2007 sur l'accueil des demandeurs d'asile et de certaines autres catégories d'étrangers sur la politique de retour proactive [Law of 12 May 2024 amending the law of 15 December 1980 on access to the territory, stay, establishment and removal of foreigners and the law of 12 January 2007 on the reception of asylum seekers and certain other categories of foreigners on the proactive return policy], 12 May 2024.

- 410

European Union, Court of Justice of the European Union [CJEU], WS v State Agency for Refugees under the Council of Ministers (SAR), C-621/21, ECLI:EU:C:2024:47, 16 January 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database.

- 411

European Union, Court of Justice of the European Union [CJEU], K and L v State Secretary for Justice and Security (Staatssecretaris van Justitie en Veiligheid), C-646/21, ECLI:EU:C:2024:487, 11 June 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database.

- 412

European Union, Court of Justice of the European Union [CJEU], AH (C‑608/22),FN (C‑609/22) v Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (Bundesamt für Fremdenwesen und Asyl‚ BFA), Joined Cases C-608/22 and C-609/22, ECLI:EU:C:2024:828, 04 October 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database.

- 413

Decisions from the Austrian Supreme Court following the CJEU decision in C-608/22 and C-609/22: Austria, Supreme Administrative Court [Verwaltungsgerichtshof - VwGH], Applicant v Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (Bundesamt für Fremdenwesen und Asyl‚ BFA), Ra 2021/20/0425-21, 23 October 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database. Austria, Supreme Administrative Court [Verwaltungsgerichtshof - VwGH], Applicant v Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (Bundesamt für Fremdenwesen und Asyl‚ BFA), Ra 2022/20/0028-18, 23 October 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database.

- 414

European Union Agency for Asylum. (February 2025). Jurisprudence related to Gender-Based Violence against Women: Analysis of Case Law from 2020-2024.

- 415

Arrêté du 6 février 2024 pris pour l'application des articles L. 531-11 et L. 561-8 du code de l'entrée et du séjour des étrangers et du droit d'asile et définissant les modalités de l'examen médical prévu pour les personnes susceptibles de bénéficier ou qui bénéficient d'une protection au regard des risques de mutilation sexuelle qu'elles encourent [Order of 6 February 2024 issued for the application of Articles L. 531-11 and L. 561-8 of the Code of Entry and Residence of Foreigners and the Right to Asylum and defining the procedures for the medical examination provided for persons likely to benefit or who benefit from protection with regard to the risks of sexual mutilation that they incur], 6 February 2024. French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons | Office français de protection des réfugiés et apatrides. (2024, February 23). Le focus mutilations sexuelles féminines [FGM in focus].

- 416

French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons | Office français de protection des réfugiés et apatrides. (2024, March 4). Une nouvelle rubrique dédiée aux professionnels de santé [New information section for medical professionals].

- 417

- 418

European Union Agency for Asylum. (January 2024). Persons with Disabilities in Asylum and Reception Systems: A Comprehensive Overview. European Union Agency for Asylum. (2024, January 18). Displaced Ukrainians with Disabilities Seeking Temporary Protection in Europe. Situational Update No 20.

- 419

Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons | Commissariaatgeneraal voor de vluchtelingen en de staatlozen | Commissariat Général aux Réfugiés et aux Apatrides. (2024, June 28). CGRS project ‘Vulnerability and asylum: applicants for international protection’.

- 420

United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. (2024, April 29). Concluding observations on the combined second and third periodic reports of Sweden. CRPD/C/SWE/CO/2-3. United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. (2024, September 30). Concluding observations on the combined second and third periodic reports of Belgium. CRPD/C/BEL/CO/2-3. United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. (2024, October 8). Concluding observations on the combined second and third periodic reports of Denmark. CRPD/C/DNK/CO/2-3.

- 421

Arca di Noè Società Cooperativa Sociale. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025.

- 422

Cyprus, International Protection Administrative Court [Διοικητικό Δικαστήριο Διεθνούς Προστασίας], B. F. v Republic of Cyprus through the Asylum Service (Κυπριακή Δημοκρατία και/ή μέσω Υπηρεσίας Ασύλου), No 1976/22, 29 March 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database.

- 423

European Council on Refugees and Exiles. The rights of refugees and asylum applicants with disabilities: Article 26 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and Beyond.

- 424

FENIX Humanitarian Legal Aid et al. (2024, February 6). LGBTQI+ Asylum Seekers in Greece. Swedish Federation for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex Rights | Riksförbundet för homosexuellas, bisexuellas, transpersoners, queeras och intersexpersoners rättigheter, & Queer Youth Sweden | RFSL Ungdom. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025.

- 425

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA). (2024). LGBTIQ equality at a crossroads - Progress and challenges.

- 426

European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA). (November 2024). Applicants with diverse sexual orientations, gender identities, gender expressions and sex characteristics. Cross-cutting elements; European Union Agency for Asylum. (November 2024); Applicants with diverse sexual orientations, gender identities, gender expressions and sex characteristics. Examination procedure; European Union Agency for Asylum. (November 2024). Applicants with diverse sexual orientations, gender identities, gender expressions and sex characteristics. Reception; European Union Agency for Asylum. (November 2024). Applicants with diverse sexual orientations, gender identities, gender expressions and sex characteristics. Information note.

- 427

EUAA Case Law Database. Gender identity/Gender expression/Sexual orientation/SOGIESC. 2024.

- 428

Striking Sirens Coalition. (2024, September 20). Believe it or not: International asylum conference on credibility assessment in SOGIESC cases. Swedish Federation for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex Rights | Riksförbundet för homosexuellas, bisexuellas, transpersoners, queeras och intersexpersoners rättigheter, & Queer Youth Sweden | RFSL Ungdom. (2024). Input to the Asylum Report 2025.

- 429

Danish Immigration Service | Udlændingestyrelsen. (2024, November 15). Vejledning om indkvartering af LGBT+ personer [Guidance on accommodation for LGBT+ people].