COMMON ANALYSIS

Last update: June 2025

In mid-April 2023, hostilities broke out between the SAF, and the RSF. This conflict follows several years of rivalry between these two components of the Sudan’s security apparatus, whose respective leaders took the helm of the state as president and vice-president of the Transitional Sovereignty Council following the fall of the 30-year-long dictator Omar Hassan al-Bashir in 2019. After working together to overthrow the civilian-led government in October 2021, growing tensions between the two leaders crystallised over the timeline for the integration of the RSF into the military and led to the outbreak of an open and nationwide conflict that quickly spread from Khartoum to large parts of the country, notably Darfur, the Kordofans and Al Jazirah.

Fuelled by an inflow of weapons and military equipment from foreign actors despite an existing UN arms embargo on Darfur, the conflict has led to what is often described as the world’s largest current humanitarian crisis and one of the most severe on record. As of March 2025, 8.5 million people have been internally displaced as a result of the conflict, while a further 3.9 million have fled to neighbouring countries. More than half of the total population, or 25 million people, were facing acute food insecurity at that time.

Several initiatives, including a UN Security Council resolution calling for an immediate end of hostilities in March 2024, have been launched to end the conflict but the few commitments made have remained largely unimplemented as both the SAF and the RSF continue to pursue their war aims.

The conflict has become more and more complex and volatile with the use of new military equipment, such as armed drones whose long range has disrupted the frontlines, rendering previously safe areas vulnerable to devastating attacks. Also, both warring parties have massively recruited civilians, often along ethnic lines. Both sides have been accused of human rights abuses, indiscriminate attacks against civilians, as well as war crimes and crimes against humanity, with the RSF more often identified as the perpetrator.

[COI reference: Country Focus 2024, 1.1.1., 1.3.3.; Country Focus 2025, 2.5.; Security 2025, 1.1.1., 1.1.2.; COI Update 2025, 3.]

COMMON ANALYSIS

Last update: June 2025

For a general overview of the main actors of serious harms and their areas of control in Sudan involved in the current conflict, please see 2. Actors of persecution or serious harm.

During the reference period, the country has been fragmented into different areas of control with most territories being held by either the SAF or the RSF, who remain the primary parties to the conflict, alongside local armed groups controlling regional territories such as the SPLM-N-al-Hilu in the Kordofans and Blue Nile as well as factions of SLM in Darfur.

The SAF retained control over the country’s north, east and southeast, including Port Sudan on the Red Sea Coast. Meanwhile, the RSF has been controlling most of the city of Khartoum from April 2023 until March 2025, when the SAF regained control of the capital city Khartoum and key strategic locations. Between January and March 2025, the SAF retook from the RSF Wad Madani and most of the Al Jazirah state’s territory as well as most of Sennar state. Also, the RSF controls large parts of West and North Kordofan as well as the Darfur region except for El Fasher state capital, and some parts of North Darfur. Meanwhile, the SLM-AW which declared itself neutral in the current conflict, has continuously controlled parts of the Jebel Marra in Darfur, and SPLM-N-Al-Hilu controlled parts of Blue Nile and South Kordofan states.

As the only belligerent to own combat aircrafts, the SAF carried out all the airstrikes since the eruption of the conflict and relied on its air superiority combined with artillery strikes and the deployment of tanks to defend fixed positions and break the siege of its garrisons despite its lack of troops on the ground to pursue RSF troops in urban terrain. As the conflict progressed, the SAF deployed new combat drones acquired from Türkiye and Iran and used them to conduct mass drone attacks supporting its ground-based offensives. SAF has also reportedly used chemical weapons on at least two occasions, alongside ‘indiscriminate bombing’ of civilian infrastructure, attacks on schools, markets and hospitals and extrajudicial executions.

In contrast, relying on the mobility and agility of its troops, the RSF has adopted hit-and-run tactics to target SAF positions and loot their resources and gain access to additional heavy weapons such as artillery and long-range missiles. With the logistical support and weapons supply from regional powers such as Russia’s Wagner Group or the UAE, although the UAE government denies it, the RSF also gained sophisticated intelligence capabilities and access to combat drones. They used these abilities to spy on army’s movements and take further advantage of their lack of hierarchical chain of command that allow the RSF to regroup and redeploy their troops following the necessities on the ground. In addition, the drones were used to strike areas far away from the frontlines with the aim of creating a sense of constant threat throughout the country and stretching the SAF's defensive positions. These tactics enabled the RSF and allied militias to force the SAF’s retreat of some positions and take control of vast territories during the first year of the conflict, particularly in Greater Khartoum, Darfur and Al-Jazirah. Reportedly, the RSF continued to employ tactics known from the Janjaweed era, including pillaging and looting, as well as deliberate killings to intimidate residents.

Sources have highlighted the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war, defined as a characteristic of the ongoing conflict, with widespread instances of rape and gang-rape, primarily targeting women and girls. These acts have been particularly prevalent during city invasions, attacks on IDPs and their camps, and when armed groups occupied urban areas, especially at the hands of the RSF. Additionally, UN special rapporteurs noted in June 2024 that both the SAF and the RSF are using food as a weapon of war, blocking aid deliveries, starving the civilian population and disrupting farming activities, increasing significantly the risk of a looming famine. See 3.3. Members of the Resistance committees (RCs) and Emergency Response Rooms (ERRs), 3.7. Humanitarian and healthcare workers, and 3.9. Women and girls.

[COI reference: Country Focus 2024, 1.1.3.; Security 2025, 1.2.1.; COI Update 2025, 2.1.]

Data concerning this indicator are primarily based on ACLED reporting from 15 April 2023 to 21 March 2025.

Also, as reported by sources, including ACLED, these figures are likely to be underestimates, as incidents and fatalities might not be officially recorded by local and health authorities due to the ongoing conflict. For more information on the methodologies of data collection, please see Country Focus 2024, Security 2025 and COI Update 2025.

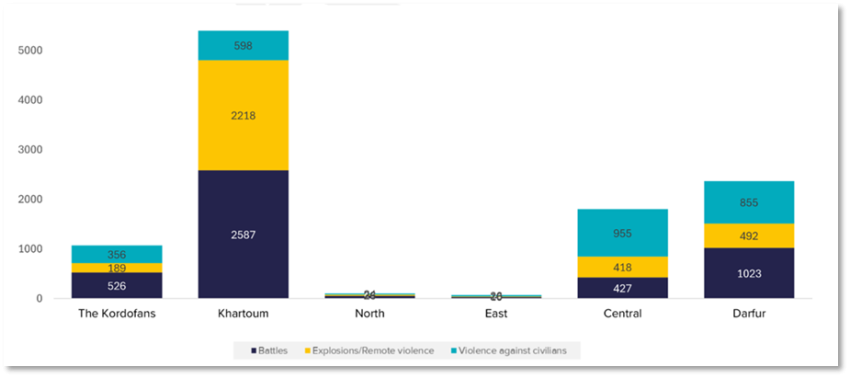

In Sudan, 10 567 security incidents were reported of which 4 597 were recorded as battles, 3 299 as explosions/remote violence and 2 671 as incidents of violence against civilians.

Security incidents were recorded in all regions, with Khartoum (5 330), Darfur (2 294), the Central (1 774) and the Kordofans (992) registering the highest numbers during the reference period. In 3 587 instances civilians were the primary or only target.

Based on ACLED data, further calculations on security incidents per week in each region for the period are also provided in the section b).

Figure 2: Breakdown by region of number of incidents recorded by ACLED between 15 April 2023 and 21 March 2025.

Source: EUAA elaboration based on ACLED data as of 21 March 2025.

[COI reference: Country Focus 2024, 1.1.3; Security 2025, 1.1.4.; COI Update 2025, 2.2.]

COMMON ANALYSIS

Last update: June 2025

Data concerning this indicator are primarily based on ACLED reporting from 15 April 2023 to 21 March 2025.

The number of civilian casualties is considered a key indicator when assessing the level of indiscriminate violence and the associated risk for civilians in the context of Article 15(c) QD/QR.

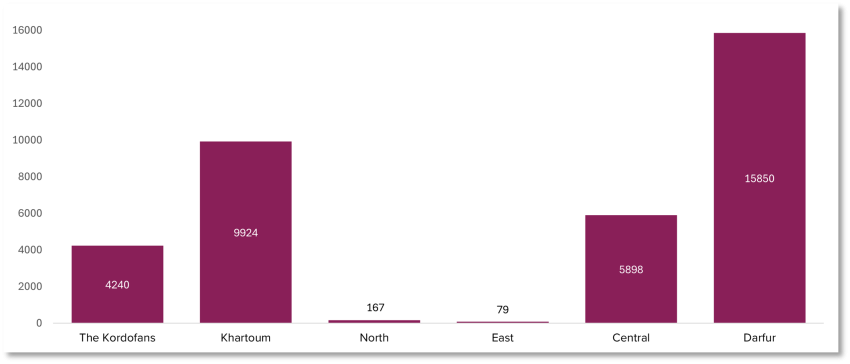

As no comprehensive data with regard to civilian deaths and injuries at the level of the regions in Sudan has been identified, this analysis refers to ACLED records regarding the overall number of fatalities. The data used for this indicator reflects the number of fatalities in relation to reported ‘battles’, ‘violence against civilians’ and ‘explosions/remote violence’ with reference to the ACLED Codebook. Importantly, it does not differentiate between civilians and combatants and does not additionally capture the number of those injured in relation to such incidents. While this does not directly meet the information needs under the indicator ‘civilian casualties’, it can nevertheless be seen as a relevant indication of the level of confrontations and degree of violence taking place.

It should further be mentioned that ACLED data are regarded as merely estimates, especially with regard to the number of fatalities. As reported by sources, including ACLED, these figures are likely to be underestimates, as incidents and fatalities might not be officially recorded by local and health authorities due to the ongoing conflict. Please note that the reported number of fatalities is further weighted by the available estimations of population of the respective region provided by different sources. This data is presented as the approximate number of fatalities per 100 000 inhabitants.

See clarifications in Country Focus 2024, Security 2025 and COI Update 2025.

In total 28 608 fatalities were reported in Sudan. Other sources suggest that as of May 2024, up to 150 000 people have been killed since the beginning of the ongoing conflict. However, besides telecommunication blackouts and insecurity reportedly hampering the recording of fatalities, many indirect cases of death resulting from war-exacerbated factors – such as lack of emergency care, essential food, medicine and vaccination programmes – were not recorded. Fatalities were reported in all regions, with Darfur (13 354 ), Khartoum (9709 ), the Kordofans (4 010 ), and the Central (5 765 ) registering the highest numbers during the reference period. Urban residential areas have been the most impacted locations (e.g. attacks on markets being the most injurious for civilians).

As of January 2024, according to Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) civilians accounted for 99 % of the recorded casualties, with 57 % of the incidents occurring in urban residential areas, and 80 % of incidents attributed to airstrikes. According to this estimate, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) suggested that the death toll in other parts of the country must have also been considerably higher than the respective recorded figures.

Based on ACLED data, further calculations on fatalities per 100 000 inhabitants in each region for the period are also provided in the section b).

Figure 3: Breakdown by region of number of casualties recorded by ACLED between 15 April 2023 and 21 March 2025.

Source: EUAA elaboration based on ACLED data as of 21 March 2025.

[COI reference: Country Focus 2024, 1.1.3; Security 2025, 1.1.4; COI Update, 2.2.]

COMMON ANALYSIS

Last update: June 2025

Data concerning this indicator is mostly based on IOM and UNHCR reporting.

For more information on the methodologies of data collection please see Country Focus 2024, Security 2025 and COI Update 2025.

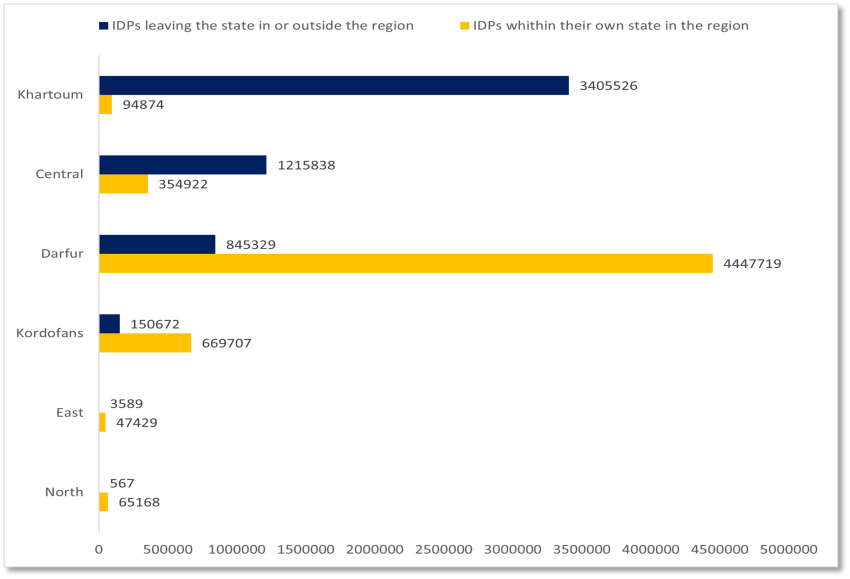

According to IOM and UNHCR, as of the start of March 2025, about 11.3 million people have been forcibly displaced as a result of the ongoing conflict, of whom more than 8.5 million were internally displaced while 3.9 million have fled Sudan to neighbouring countries. According to UNICEF, the number of displaced children (internally and abroad) amounted to 5 million as of September 2024.

An estimated 3.8 million persons were already internally displaced (IDPs) in Sudan prior to the 15 April 2023, of whom more than 1 million had experienced secondary displacement as a result of the ongoing conflict at the beginning of December 2024. At this date, Sudan was hosting a total estimated IDP population of 11.5 million people. More than half of them (53 %) were children under the age of 18 years and 55 % were female.

According to IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) Data, as of December 2024, IDPs had been displaced to 9 653 locations across all 18 states of the country, with the majority of the IDPs being sheltered by hosting families and communities.

Figure 4: Breakdown by region of number of IDPs recorded by IOM as of 12 March 2025.

Source: EUAA elaboration based on IOM data.

[COI reference: Country Focus 2024, 1.1.1, 1.1.5; Security 2025, 1.3.1; COI Update, 3.1.1.]

COMMON ANALYSIS

Last update: June 2025

Beyond the elements described above, the ongoing conflict has a global impact on the life of civilians living in Sudan as it has led to one of the most severe humanitarian crises in records with almost two thirds of the population in ‘desperate need’ of humanitarian and protection assistance. Attacks on civilian areas and infrastructure have seriously impacted healthcare system, agriculture activities, food chain, water and sanitation systems. It resulted in telecommunication blackouts, food stock looting, and school closures. According to UNICEF, as of September 2024 more than 17 million children were not attending school, and more than 3 200 school buildings were being used as shelters for IDPs.

A large proportion of the health facilities have been destroyed or rendered inoperable, while health workers have been targeted by both warring parties. As a result, the civilian population is experiencing serious difficulties in accessing health care and medical supplies, with two-thirds of the population no longer able to access essential health services.

The conflict has also led to the collapse of the economy and the disruption of the food and water supply chains, placing an unprecedented number of people in situation of starvation and famine. As of December 2024, more than half of the total population, or over 25 million people, were facing acute food insecurity and famine was confirmed in at least five areas.

This situation is further exacerbated by road blockages of certain localities and the obstructions and restrictions imposed on humanitarian aid deliveries by the belligerents, who have also been targeting aid workers. For more information, please see 3.7. Humanitarian and healthcare workers. Lack of food, income and access to basic services led IDPs to accept risky jobs to cover their needs. IOM identified multiple specific protection risks including trafficking of persons, child marriage, forced recruitment, child labour and sexual violence. For more information, please see 3.2. Individuals fearing forced recruitment by the RSF, 3.9. Women and girls, and 3.10. Children.

Many roads are under the threat of attacks and simply inaccessible while insecurity, administrative obstacles and/or poor road conditions is generally reported. Both the SAF and the RSF and their allies have set up many checkpoints in their respective areas of control, which are used to control the population but also as a mean of looting. Multiple checkpoints are usually along a same road, restraining movements and extending journey times. Reports indicate that people passing through checkpoints face extorsion, mistreatments, sexual violence and specific targeting, notably on the basis of ethnicity, age or profession.

Explosive remnants of war have been reported in some areas of the country because of the widespread use of conventional weapons including field artillery, mortars, air-dropped weapons and anti-aircraft guns during the clashes, notably in urban areas of El Obeid, in North Kordofan, in Omdurman and rural areas North of Bahri. The RSF has also been accused of planting mines, especially in northern Bahri.

[COI reference: Country Focus 2024, 1.1.5., 1.2.4.; Country Focus 2025, 3.2.4; Security 2025, 1.3.1., 2.1.5.]

It should, furthermore, be noted that the COI used as a basis for this assessment cannot be considered a complete representation of the extent of indiscriminate violence and its impact on the life of civilians.

In view of the ongoing conflict, the situation remains fluid and changes in trends may be observed in the future. It should be highlighted that in Sudan the widespread crackdown on media outlets, along with the recurring communication blackouts significantly impacted the reporting and the conflict media coverage throughout the country.

Therefore, concerns with regard to underreporting, especially pertinent to the quantitative indicators, should be taken into account.