|

⚠ |

|

Please note that this country guidance document has been replaced by a more recent one. The latest versions of country guidance documents are available at /country-guidance. |

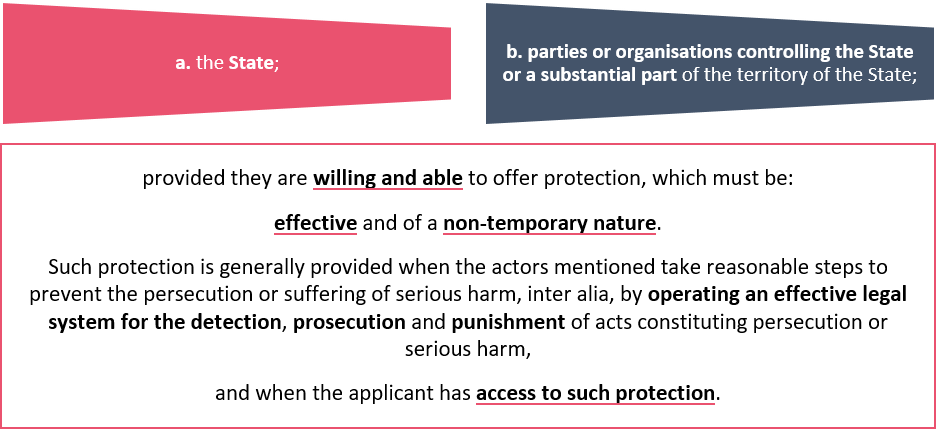

Article 7 QD stipulates that protection can be provided by:

In general, the judiciary in Afghanistan is described as underfunded, understaffed, inadequately trained, largely ineffective, and as subject to threats, bias, political influence, and pervasive corruption. The general insecurity, threats, and targeted attacks on employees in the judiciary sector are additional challenges to provide justice services.

Despite the existence of a formal justice system, many disputes, ranging from disagreements over land to criminal acts, are settled outside of the formal court system by informal justice mechanisms, such as jirgas and shuras. Traditional justice mechanisms remained the main recourse for many, especially in rural areas. However, traditional and informal forms of justice continued to be implemented in Afghanistan contrary to the principle of the rule of law, human rights standards and Afghan laws.

The capability of the Government in Afghanistan to protect human rights is also undermined in many districts by the prevailing insecurity and the high number of attacks by insurgents. Although the Afghan government maintained its control in Kabul, provincial capitals, major population centres, most district centres, and most portions of major ground lines of communications, the Taliban threatened district centres and contested several positions of main ground lines of communications.

Police presence is stronger in the cities and police officers are required to follow guidelines such as the ANP Code of Conduct and Use of Force Policy. However, police response is characterised as unreliable and inconsistent, the police has a weak investigative capacity, lacking forensic training and technical knowledge. The police force is also accused of widespread corruption, involvement in organised crime, patronage, and abuse of power.

The World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index 2020 ranks Afghanistan 122nd out of 128 countries, allocating it to the last place in the ‘order and security’ factor.

Many areas in Afghanistan are influenced by insurgent groups; however, the Taliban are the only insurgent group controlling substantial parts of the territory and controlling certain public services, such as healthcare and education, in those areas. In 2020, in territories under their control, the group continued to operate a parallel justice system based on a strict interpretation of the Sharia, leading to executions by shadow courts and punishments deemed by UNAMA to be cruel, inhumane, and degrading. An increasing number of Afghans across the country were reported to seek justice in Taliban courts due to feeling frustrated with the State’s bureaucracy, corruption, and lengthy processing times.

Where no actor of protection meeting the requirements of Article 7 QD can be identified in the home area of the applicant, the assessment may proceed with examination of the availability of internal protection alternative.