| Data on unaccompanied minors 629 |

At EU+ level, the only available statistics on vulnerable applicants collected in a comparable manner are numbers of unaccompanied minors 630 (UAMs 631 ).

In 2018, some 20 325 UAMs applied for international protection in the EU+, some 37 % fewer than in 2017. The drop in the number of UAM applicants was, thus, much sharper than that in the overall number of applications. The share of UAMs relative to all applicants was 3 %, similarly to 2017. Almost three quarters of all applications were lodged in just five EU+ countries: Germany (20 %), Italy (19 %), the United Kingdom (14 %), Greece (13 %) and the Netherlands (6 %).

In 2018 the number of UAMs continued to decrease but this was not the case in all EU+ countries. Notably, many more UAMs applied for international protection in Slovenia (+ 42 %), the United Kingdom (+ 30 %) and France (+ 25 %). In contrast, UAM applications dropped massively in Austria (- 71 %), Italy (- 61 %, after the record levels of 2017) and Germany (- 55 %). Notwithstanding the large decrease, the latter two countries continued to receive the most UAM applications. In some EU+ countries, UAMs represented non-negligible proportions of asylum applicants in 2018: in particular, they accounted for almost one in five applications in Slovenia and Bulgaria, and for almost one in ten in the United Kingdom, Denmark, Italy and Romania.

About half of all UAM applicants were from five countries of origin: Afghanistan (16 % of all UAM applicants in the EU+), Eritrea (10 %) Syria, Pakistan (7 % each) and Guinea (6 %) (Figure 30). Compared to a year earlier, the number of UAMs dropped among all citizenships, except for nationals of Tunisia (among whom they almost tripled), Congo DR (+ 50 %), Iran (+ 25 %), Vietnam (+ 19 %) and Sudan (+ 18 %). In contrast, UAM applications almost halved for Bangladeshis and nationals of several Western African countries, including Gambia, Ghana, Senegal and Nigeria; for all these citizenships, the drop was more evident in Italy.

|

Number of UAMs in 2018 and 2017 by citizenships and relative change |

| Figure 30: In 2018, a lower number of UAMs applied for international protection than in 2017 |

Among the ten countries of origin accounting for most UAM applications, those with the largest concentration were all located in Africa: Gambia (almost one in five applicants were UAMs), Eritrea (one in ten), Guinea, Somalia and Sudan (almost one in ten) (Figure 31). Beyond the top ten, however, high proportions of unaccompanied minors were observed also among nationals of Vietnam (13 %) and Cambodia (11 %).

|

Share of UAMs to total number of applicants by country of origin, 2018 |

| Figure 31: For some citizenships, the share of UAMs was considerably higher, suggesting a higher degree of vulnerability |

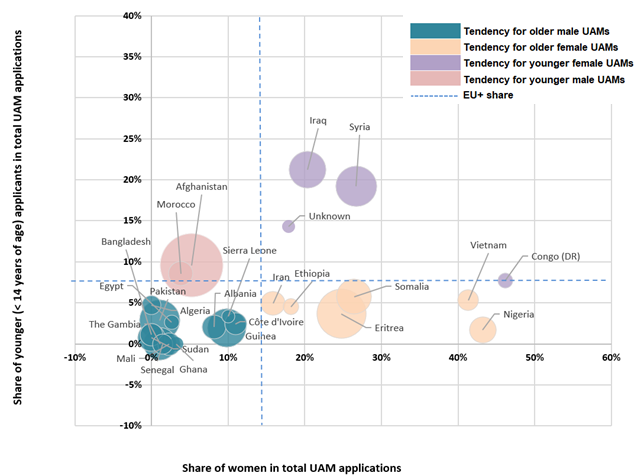

The overwhelming majority of UAMs lodging an application in 2018 were male (86 %), similarly to the previous years. Nevertheless, the proportion of females among UAMs was relatively higher for some countries of origin: this was the case for Congo DR, Nigeria and Vietnam, among whom almost half of UAMs were female (Figure 32). In terms of age of applicants, Iraqi and Syrians had the largest proportion of UAM applicants being younger than 14 years old. 632 Female UAMs tended to be relatively younger than males: almost one in five female UAMs were in fact younger than 14 years old. Moreover, two out of five female UAMs were younger than 14 years old among Iraqis, and one in three among Afghans or Syrians.

|

Share of female UAMs (x-axis) and share of UAMs younger than 14 years old (y-axis) in total UAM applicants |

|

| Figure 32: The proportion of UAM applicants younger than 14 years old was larger among females than males |

| Specialized reception |

In Belgium, mixed trends were noted regarding specialised reception capacity for unaccompanied minors. Due to the reduction in the overall reception capacity for applicants for international protection and increases in occupancy rates of remaining reception facilities, a decision was made to accommodate, from September 2018 on, as an exceptional and temporary measure, four groups of adults along with unaccompanied minors: vulnerable young adults; adolescents, who stay with their parents; families; and couples, for whom living with adolescents could be considered. However, the capacity of the first reception phase in the Observation and Orientation Centres increased in the course of 2018, due to the increased inflow of unaccompanied minors. Furthermore, in 2018 and early 2019, building on previous agreements, Fedasil signed two new agreements with the Flemish and the French communities, this time of indefinite duration, on regional authorities co-financing the reception of unaccompanied minors. The agreements apply to UAMs younger than 15 years of age, or UAMs older than 15 years for who a clear vulnerability is established, or siblings of whom one of the two is a UAM of less than 15 years. Unaccompanied minors, who are beneficiaries of protection and are 16 years of age or older, are prepared with the assistance of their guardian, to live in a more autonomous setting, in individual reception structures managed by partner organisations in Fedasil’s reception network. It is important to note that these young people are placed in small family-scale reception centers" (capacity between 10 and 15 UAMs) in cooperation with regular youth care organisations. Overall, a number of activities implemented by the Flemish, French, and German communities in 2018 aimed at coaching and preparing unaccompanied minors to live independently. 633

In Bulgaria, ‘secure zones’ for unaccompanied children with capacity of 100 places were constructed in the registration and reception centre in Sofia. In Italy, Article 12 of Law n.132 of 1 December 2018 specifies that unaccompanied minors still have the right to stay in SIPROIMI (ex SPRAR), until the process of their international protection application is finalised. They are accommodated in dedicated reception shelters and receive specialised services. The Refugee Reception Centre in Lithuania took steps toward improving living and care conditions in facilities hosting unaccompanied minors. These included the refurbishment of kitchen facilities and the creation of a resting area. A separate housing unit to accommodate older unaccompanied minors, who have been already granted protection status, was established in Slovenia. In this unit, psychosocial assistance is provided in a tailor-made approach to cater more effectively to individual needs.

| Legal guardianship and foster care |

In Belgium, the Royal Decree of 6 December 2018 amending the Royal Decree of 22 December 2003 implementing Title XIII, Chapter 6 Guardianship of unaccompanied minor foreigners, of the Programme Law of 24 December 2002 increased the allowance granted to guardians' associations with which the Guardianship Service has a protocol agreement. Moreover, the Guardianship Service started the implementation of the AMIF project Strengthening the Guardianship System (Versterken van het voogdijstelsel), which aims to develop a method for the monitoring of guardians, a methodology regarding the sustainable solution for UAMs, and the follow-up of challenging guardianships. A coaching programme for Dutch-speaking guardians started in 2018, to couple the already existing programme for French-speaking guardians. Through this programme, support is provided to private guardians by means of: a) a helpdesk that can be reached by phone or email; b) individualised support for challenging cases; c) a coaching trajectory for new guardians; and d) advanced training for guardians. In the Flemish community, further investments were made in 2018 toward enhancing collaboration among all actors involved in foster care to coordinate the provision of assistance to unaccompanied minors. The Flemish Foster Care consolidated the Alternative Family Care (ALFACA) method in their regular operations, while a number of activities were implemented in support of the placement of unaccompanied minors in a culture-related or kinship foster family.

Since February 2018, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, and the Netherlands participate in the Alternative Family Care II project (ALFACA II), which aims to improve the reception and care for unaccompanied minors by increasing the quality and quantity of family-based care for them.634 A similar project is the ‘Fostering Across Borders project’ (2018-2019), which is funded by the European Union’s Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme (2014-2020) with the aim of improving and expanding the provision of family-based care for unaccompanied migrant children in Austria, Belgium, Greece, Luxembourg, Poland and the United Kingdom.

In the Czechia, authorities enhanced their cooperation with the non-profit sector in the area of host care and a new system was put in place for the provision of this form of substitute care for unaccompanied minors. The Federal Government, in Germany, implemented a project to maintain foster families, legal guardianship and personal sponsorship and promote the integration of unaccompanied minors. The new Protocol on the treatment of unaccompanied minors, adopted in Croatia in 2018, offers detailed provision for guardianship and establishes the Interdepartmental Commission for the protection of unaccompanied children. Moreover, in the new Foster Care Act (OG No 115/18), in force as of January 2019, the accommodation of unaccompanied minors into foster families is provided for. In Latvia, the State Border Guard, in cooperation with the State Inspectorate for the Protection of Children's Rights, developed guidelines on Ensuring representation of foreign unaccompanied minors and asylum seekers and cooperation with authorities involved.635 The aim is to establish an effective system for the protection of unaccompanied minors and foster practical co-operation between institutions performing procedural activities related to minor foreigners and institutions representing interests and rights of unaccompanied minors. Moreover, in Poland, amendments introduced to Article 61 of the Act on Granting Protection to Foreigners, now make it possible to submit an application for placement in foster custody immediately after an unaccompanied minor expresses the intention to submit an application for international protection. Per previous practice, this would take place only after an applications was submitted. In addition, these amendments made possible the submission of application for placement under custody over a minor by the adult accompanying them, if that adult is a second-degree direct-line relative (grant parents), or second-degree indirect-line relative (siblings), or third-degree relative (aunt/uncle), for as long as the procedure for placing a minor under foster custody are ongoing.

| Processing of applications and procedural safeguards |

In Belgium, the law of 21 November 2017 amending the Immigration Act and the Reception Act, which came into force in March 2018, introduced provisions aimed at identifying more systematically and as early as possible applicants with special needs, through a detailed questionnaire on procedural needs to be filled out by the Immigration office and also through the detection of special needs in reception facilities. The new law, in Article 37, further specifies the criterion of the ‘best interest of the child’, by explicitly defining what needs to be taken into consideration when assessing a minor’s interest:

|

The law of 21 November 2017, also, provides explicitly for the right for dependent children of an applicant to be interviewed individually by CGRS and/or to lodge a separate asylum application. This provision aims at addressing situations, where the minor is best served by an individual request, such as cases where parents are a threat to the minor.

Furthermore, the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons (GCRS) moved into new premises, now equipped with eight specialised interview rooms for children with interactive tools. These include wall panels, which minors can use to convey information such as their travel route, daily life, family composition, feelings, etc. Other panels with pictures are also available, for example with pictures of different clothing styles allowing the minor to indicate how someone was dressed, as well as drawing paper, pencils and Duplo dolls to facilitate the conversation. Similar changes were introduced in the new premises of the Immigration Office. Moreover, a separate waiting room for unaccompanied minors was set up in the temporary arrival centre in Petit Chateau/Klein Kasteeltje, where unaccompanied minors are supervised at all time during the registration process until they are taken care of by Fedasil. Finally, since 2018, the Unaccompanied Minors Unit of the Immigration Office, also conducts interviews with adult family members in the context of Article 8 of the Dublin Regulation to ensure that the best interest of the minor is taken into consideration.

In Germany, following an amendment to the Social Code (SGB), Book VIII, Section 42, the social welfare offices now have the possibility and the duty to lodge an asylum application on behalf of the UAM, when there is a reason to believe that the minor is in need of international protection.

In Bulgaria, special rooms for interviewing unaccompanied minors were created in registration and reception centres in Sofia and Harmanli with a focus on offering a relaxed peaceful environment. Apart from the interview, in these rooms, rapid and complete assessment of the best interest of the child is conducted. In addition, the State Agency for Child Protection, in cooperation with all responsible institutions and organisations, developed a coordination mechanism for interaction among the various stakeholders working with UAMs. In August 2018, the Croatian government adopted a new protocol on the treatment of unaccompanied minors with a focus on timely and effective protection of the best interest of the child in the context of asylum. Similarly, in Lithuania, the Director of the Refugee Reception Centre approved a standardised form for the assessment of the best interest of unaccompanied minors. In Luxembourg, Bill No 7238 Law Proposal aims at amending several provisions related to return of the Immigration Law, including an amendment noting that a multidisciplinary team needs to evaluate the best interest of the child on a case-by-case basis when a decision is made concerning the return of an unaccompanied minor. In addition, the Swedish Migration agency produced new guidelines to support staff dealing with unaccompanied minor applicants, who have turned 18 years old.

Finally, in Greece, the responsibility for the protection of unaccompanied and separated minors has passed from the Ministry of Migration to the Ministry of Labour, Social Security and Social Solidarity.

| Strengthening / improving protection |

In Belgium, to improve care and protection of unaccompanied minors, Fedasil subsidised a number of projects, under AMIF 2018-2019, with a focus on psychological accompaniment of minors, psychotherapeutic reception (including cultural child psychiatry and trauma-therapeutic care), and staff resilience in responding to complex situations or emergencies. Under national funding, another 17 projects were selected in 2018 by Fedasil for implementation with foci ranging from sports and leisure activities to restorative practices. 636

In Bulgaria, the State Agency for Refugees started providing free transport to minors, including unaccompanied minors, to state and municipal schools. In Cyprus, the Pedagogical Institute implemented an AMIF-funded project delivering free Greek language courses to minors residing at the Kofinou centre and children residing at the centres for unaccompanied minors.

The new government, in Luxembourg, committed to pay particular attention to unaccompanied minors and the respect for the best interest of the child. The Directorate of Immigration under the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs will collaborate with the National Childhood Office to ensure the existence of specific structures for unaccompanied minors and the effective delivery of needed services to address their needs.637 In addition, the Danish Parliament has adopted new legislation that enhances social supervision of accommodation at which unaccompanied child asylum seekers reside.638

In Malta, the Child Protection Law, which shall regulate the protection of minors across all areas, including in the context of asylum, passed through another part of the discussion protocol at draft level, moving closer to the enactment of the law.

In June 2018, in the Netherlands, tthe State Secretary of Justice and Security announced that measures will be introduced to address the increasing occurrence of nuisance-causing behaviours by certain asylum seekers in the context of reception. As far as facilities of the Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers (COA) is concerned, individuals exhibiting nuisance-causing behaviour will be placed in extra-counselling and supervision locations (EBTL). In view of the increasing number of incidents caused by unaccompanied minors, such measures may also apply to unaccompanied minors older than 16, upon the permission of the minor’s supervisor appointed by Stichting Nidos.639 Upon discussions among COA, the Custodial Institutions Agency (DJI) and Stichting Nidos it was decided that for unaccompanied minors for whom existing measures are not appropriate, but intervention is still needed, specialised reception and counselling will be provided – a pilot project to this end is currently under development, which will last for a year and will include a performance evaluation component. Moreover, the results of a study evaluating the reception model for unaccompanied minors were published in 2018 with overall positive results regarding the provision of services and care. One area for further improvement, as identified by the study, was counselling of unaccompanied minors, especially in ensuring that unaccompanied minors cab develop themselves optimally and independently after they turn 18. Another report, commissioned by COA and published by UNICEF, on the living conditions of children in asylum centres and family locations was published in 2018. The report included 92 recommendations addressed to COA and the Ministry of Justice, and steps have been already taken to act upon them.

Following a decision of the Norwegian parliament from November 2017, the Ministry of Justice and Public Security introduced changes, in January 2018, to the Immigration Regulations concerning unaccompanied minors. Specifically, the provision on time-limited residence permits for unaccompanied minors between 16 and 18 years old was amended to introduce a list of factors to be considered when deciding whether an unaccompanied minor should be granted a time-limited permit or a permit without such limit.

In Sweden, in June 2018, legal amendments to the temporary act regulating issues of residence permits gave, among others, unaccompanied minors, who arrived in Sweden before 25 November 2015 and had applied for asylum, the right to a residence permit for pursuing studies at upper secondary schools. These amendments were meant to regularise the legal situation of unaccompanied minors who had come to Sweden and had their applications rejected following long waiting times. Moreover, new rules regarding the placement of unaccompanied minors applying for protection into specific municipalities came into force in June 2018, following amendments to the Act on the reception of asylum seekers and others. According to the new rules a municipality, which has been assigned to receive an unaccompanied minor may place the minor concerned for accommodation in another municipality, pending that the second municipality has entered into an agreement on the placement, or in the event that for reasons related to child care needs, exceptional circumstances exist.

In Slovakia, amendments to the Act No 305/2005 Coll. on Social and Legal Protection of Children and on Social Guardianship introduced changes aimed at improving the quality of the service and the conditions in the areas of socio-legal protection and social guardianship. These changes mean a lower number of children in individual groups, more staff, and increased professional competence, which will contribute to the improvement of protection and care for unaccompanied minors.

In the UK, a new form of leave was introduced for children to ensure that those, who do not qualify for refugee or humanitarian protection leave, will still be able to remain in the UK long term. Minors obtaining this new form of leave will be able to study, work, access public funds and healthcare, and apply for settlement after five years. In addition, over the years 2016-2018, in the frames of Controlling Migration Fund, the Department for Education has contributed GBP 1.3 million to eight diverse local authorities to support initial assessment and better access to education for unaccompanied minors. These authorities, based on their experiences, also develop resources and tools that can be easily shared with other authorities catering to the needs of unaccompanied minors, which may be facing similar challenges. The Department for Education, in collaboration with the Virtual School Heads Network, supports the development of these tools, as well as examples of good practices and case studies. In addition, in July 2018, the Lord Chancellor introduced an amendment to the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 to include unaccompanied minors into the scope of legal aid fir immigration matters.640 Finally, a number of policy guidance documents in areas related to catering to the needs of unaccompanied minors in the context of asylum were updated by UK authorities in the course of 2018.641

| Age assessment |

Establishing whether an asylum seeker is a child results in significantly different treatment in a number of fields related to child protection. In 2018, in Cyprus an increase in age assessment interviews was recorded due to the increase in the number of applicants claiming to be unaccompanied minors. A large percentage of those referred for a medical age assessment exam proved to be over 18. In addition, AMIF funds were used to finance the conduct of dental exams for the purposes of age assessment. In the Czechia, through cooperation between the Ministry of the Interior, the Office of the Ombudsman, and UNHCR, a new pilot project was conducted to develop a new method of age assessment using non-medical tools. A Protocol on the treatment of unaccompanied minors, adopted by the Croatian government in 2018, includes detailed provisions for the conduct of age assessment. In 2018, the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs in Luxembourg, published information as to the conduct of age assessment for unaccompanied minors and the medical examinations that are part of the process. In the first phase, the process involves wrist and hand x-rays and, if doubts persist, in the second phase, persons concerned undergo a full physical examination, a clavicle x-ray, and dental panoramic. The Ministry further clarified that deontological rules apply during this process and that the concerned individuals are not touched.

In the Netherlands, in October 2019, the work programme of the Ministry of Justice and Security was published, where it was decided that from 2019 on, the age assessment process for unaccompanied minors, which includes the use of x-rays of the hand-wrist are, will be supervised by the Inspectorate of Justice and Security (IvenJ) in collaboration with the Inspectorate for Health and Youth Care (IGJ) and the authority for Nuclear Safety and Radiation Protection (ANVS). Moreover, the Swedish National Board of Forensic Medicine, which is responsible for medical age assessment, changed its probability scale for female applicants. Finally, an updated guidance for UK Visas and Immigration staff on how to make decisions in cases where applicants claim to be minors, but present little or no evidence, was published in October 2018.642

| Increasing capacity, enhancing competence |

A number of countries allocated more resources in order to enhance competence and invested further in improving expertise of staff when dealing with minors, oftentimes based on, but not limited to the relevant EASO modules (Belgium, Croatia, Germany, Estonia, Finland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Slovakia). In Austria, for instance, the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum organised trainings on conducting interviews with minors. Recognising the complexity of issues entailed in the effective reception of unaccompanied minors and with a view to ensuring their physical and psychological well-being, Belgian authorities adapted a complexity approach in increasing staff expertise by organising courses on group dynamics, handling aggression, deontological code when dealing with minors, suicide prevention, addressing potential radicalisation, restorative practices when dealing with conflict 643, increasing expertise in identifying minor’s school competences. In Bulgaria, training of staff focused on best interest of the child assessment, while in Finland, staff of the Asylum Unit within the Finnish Immigration Service received trainings on forced marriages, female genital mutilation, child abuse and child neglect. The Finnish Immigration service also developed new guidelines on how to deal with cases of child marriages and when/how to report child abuse and neglect.

Changes in staff numbers and compositions, as well as in financial resources allocated in catering to the needs of unaccompanied minors, were also made in a number of countries. In Belgium, due to the departure of some protection officers, the number of CGRS officers specialised in handling applications from unaccompanied minors was reduced to 90. A reduction of staff involved in the reception of unaccompanied minors also took place in Fedasil, while in the Guardianship Service, 70 new guardians were recruited. In light of the increased arrivals of unaccompanied minors in Spanish territory, authorities provided a significant budgetary reinforcement to the Autonomous Communities and the Autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla, to improve protection of minors. Steps were also taken in Lithuania towards facilitating the provision of quality therapy service for unaccompanied minors by improving working conditions for psychologists and by purchasing additional therapy equipment. In the UK, in January 2018, additional funding was announced by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government for local authorities caring for unaccompanied minors to enhance existing capacity. 644

| Intra - EU cooperation |

In the framework of an agreement, signed between Ireland and France in November 2016, to identify and relocate up to 200 unaccompanied minors from Calais to Ireland, a total of 41 young persons who expressed an interest and who were assessed as suitable under this programme have arrived in Ireland; this programme was completed in 2018. In addition, in December 2018, following an agreement between the Irish Ministers for Justice and Equality, and Children and Youth Affairs, and the Greek Minister for Migration Policy, Ireland offered to accept up to 36 unaccompanied minors in need of international protection from Greece. 645

______

629 The term ‘unaccompanied minor (UAM) refers to ‘a minor who arrives on the territory of the Member States unaccompanied by the adult responsible for them by law or by the practice of the Member State concerned, and for as long as they are not effectively taken into the care of such a person. It includes a minor who is left unaccompanied after they have entered the territory of the Member States’ (see: EMN, Glossary – unaccompanied minor, as derived from Art. 2(l) of the recast Qualification Directive.) In the present Report the term ‘unaccompanied minor’ (UAM) is used to indicate UAMs seeking asylum in the EU+ countries.

630 EU+ countries may collect statistics on other vulnerable groups applying for international protection at national level but no comparable picture can be drawn.

631 For statistical purposes, the unaccompanied minor applicants are those whose age has been accepted by the national authority, and, if carried out, confirmed by an age-assessment procedure. The Eurostat Guide for practitioners highlights that ‘the age of unaccompanied minors reported shall refer to the age accepted by the national authority. In case, the responsible national authority carries out an age assessment procedure in relation to the applicant claiming to be an unaccompanied minor, the age reported shall be the age determined by the age assessment procedure’.

632 Among the citizenships of origin with at least 200 applications lodged by unaccompanied minors.

633 For instance, the Administration générale de l’aide à la jeunesse - service MENA, and https://www.siaeupen.be .

634 The project is coordinated by Nidos (Netherlands) and the partners are Minor-Ndako (Belgium), Youth Care Service Flemish-Brabant (Belgium), Centre for missing and exploited children (Croatia), Mentor Escale (Belgium), METAdrasi (Greece), Hope for Children CRC Policy Centre (Cyprus) and Associazione Amici dei Bambini (Italy).

635 Ministry of Welfare, State Inspectorate for the Protection of Children's Rights, Guidelines for ensuring representation of unaccompanied minors and asylum seekers and for cooperation among the authorities involved, 2018 (in Latvian).

636 Please, note that most projects open to UAMs do not distinguish between UAMs applying for international protection and those who do not apply for international protection

637 DP, LSAP and déi gréng, Accord de coalition 2018-2023 (in French).

638 For more information: Institut for Menneskerettigheder, Asyl – Status 2018 (in Danish).

639 Stichting Nidos is designated in accordance with Dutch law as the agency charged with temporary guardianship of minor asylum seekers.

640 Ministry of Justice, Legal aid for immigration matters for unaccompanied children.

641 gov.uk, Unaccompanied asylum seeking children and leaving care: funding instructions; UK Home Office, Calais Leave, Version 1.0; gov.uk, Asylum seekers with care needs.

642 UK Home Office, Assessing age, Version 3.0.

643 https://vzw-oranjehuis.be. The training on restorative practices to empower UAMs and the staff of the reception centres in the prevention and sustainable handling of conflicts is provided by Ligand, a subsidiary organisation of Oranjehuis. More information on https://www.ligand.be .

644 gov.uk, Controlling Migration Fund: prospectus .

645 Department of Justice and Equality, Minister Flanagan agrees to invite up to 36 unaccompanied minors to Ireland from Greece.