Box 2. Temporary protection for displaced persons from Ukraine

As the military aggression against Ukraine persisted into its second year, millions of people seeking refuge continued to arrive in the EU throughout 2023. By 31 October 2023, over 4.3 million non-EU citizens who left Ukraine had received temporary protection in EU+ countries, with the main hosting countries being Germany, Poland and Czechia.171

Temporary protection was initially activated until 4 March 2023. It was subsequently extended on two occasions, covering the period until 4 March 2025.172Throughout 2023, all EU+ countries begun to prolong the validity of residence permits issued to beneficiaries of temporary protection or an equivalent status.iIn addition, some countries – namely Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, France, Germany, Italy and Portugal – allow temporary protection status to be converted into residence permits for employment or family reunification.173

UNHCR continued to support several EU+ countries in coordinating responses to inflows from Ukraine.iiThe Blue Dot Hubs, managed in cooperation with the United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), remained active in 2023 and engaged in providing information and assistance to persons fleeing Ukraine across Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia, as well as outside of the EU in Belarus and Moldova.174

Changes in policies and procedures governing temporary protection were introduced in 2023 in several EU+ countries. The scope of the temporary protection status was extended in 2022 in many countries to Ukrainian nationals who were already outside Ukraine when the military aggression began.175In 2023, the Constitutional Court in Austria confirmed that temporary protection applies to Ukrainian nationals who left the country shortly before 24 February 2022 but in principle were residing there.176

In contrast, measures to delimit eligibility for temporary protection were implemented in some countries in 2023, including at the appeal stage. In Finland, for example, third-country nationals who resided in Ukraine on the basis of a temporary residence permit are no longer granted temporary protection.177This was already the case in the Netherlands in 2022, but the Dutch Council of State ruled in 2024 that the State Secretary cannot end temporary protection for third-country nationals who had resided in Ukraine on a date different than specified in the EU directive. Thus, temporary protection for this group in the Netherlands ended on 4 March 2024, instead of 4 September 2023. However, after the Dutch Council of State referred questions to the CJEU for a preliminary ruling, the legal consequences of ending temporary protection on this date were frozen. This does not mean that this group continues to fall under temporary protection, but they may continue to use facilities as if they were.178

In Applicant v State Secretariat for Migration, the Swiss Federal Administrative Court ruled that temporary protection was not to be granted to Ukrainians who have EU/EFTA+ citizenship. Similarly in Norway, Ukrainians who have citizenship in a safe country no longer receive temporary collective protection,179while those who return to Ukraine may risk having their protection status revoked.180

The Administrative Court of Munich in Germany decided in Applicant v Immigration Office (M 4 S 23.2442) that unmarried partners of Ukrainians were not eligible to receive temporary protection. The court came to the same conclusion in the case M 4 K 23.2440. This latter decision was reversed by the Bavarian Higher Administrative Court on 31 October 2023, with the decision in case 10 C 23.1793.

Data on decisions granting temporary protection

The number of decisions granting temporary protection in EU+ countries is used as a proxy for data on the number of persons registering for temporary protection.

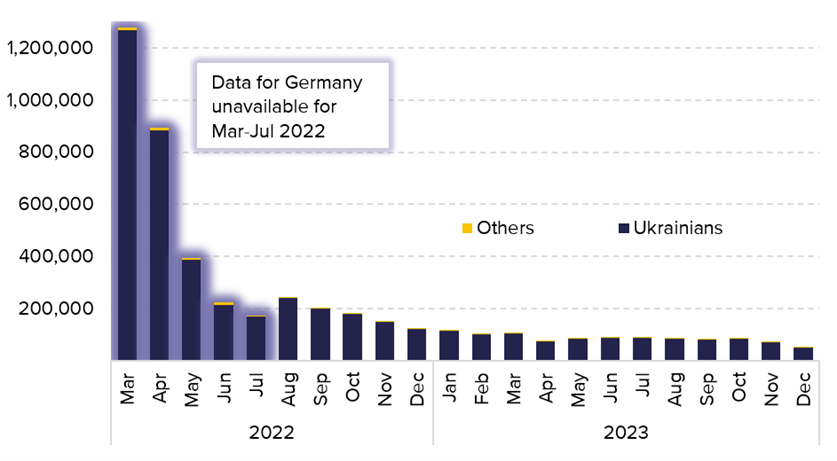

In 2023, EU+ countries issued over 1 million decisions that granted temporary protection.iiiSince the high levels at the outset of the war, decisions granting temporary protection have been declining and remained relatively stable at a lower level as of the summer of 2023 (see Figure 1).iv

Number of decisions granting temporary protection declined and have remained relatively stable

Figure 1. Number of decisions granting temporary protection in EU+ countries, March 2022–December 2023

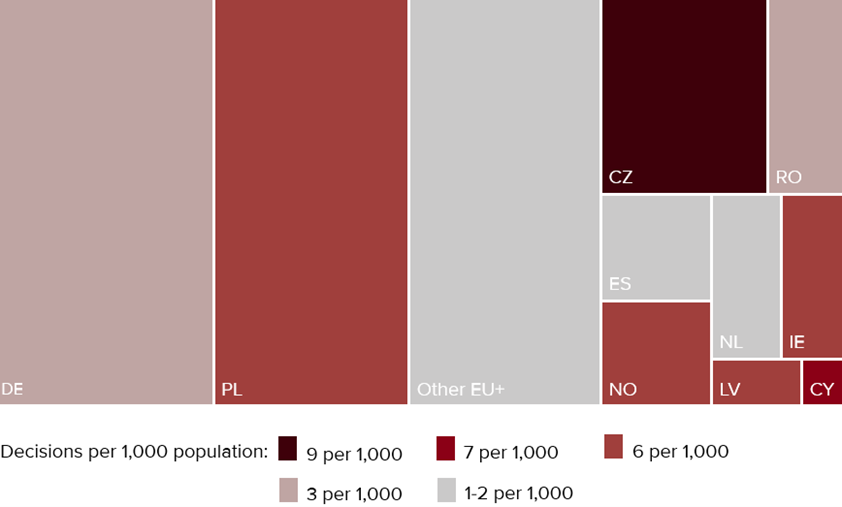

Germany (264,000) and Poland (234,000) issued the most decisions granting temporary protection in 2023, jointly accounting for almost one-half of all decisions issued in EU+ countries (see Figure 2). Many registrations were also carried out in Czechia (99,000), Romania (49,000), Spain (34,000), Norway, the Netherlands and Ireland (33,000 each) and Slovakia (30,000).

The most decisions per capita were granted by Czechia and Cyprus (9 and 7 decisions for every 1,000 inhabitants, respectively). They were followed by Estonia, Ireland, Latvia, Norway, Poland and Slovakia (with 6 decisions for every 1,000 inhabitants each).

Germany and Poland accounted for almost one-half of all decisions granting temporary protection

Figure 2. Decisions granting temporary protection by EU+ countries with most decisions in absolute values (rectangles) and most decisions per capita (legend), 2023

As in 2022, Ukrainians received 99% of all decisions granting temporary protection. In total, over 1 million Ukrainians were granted temporary protection, compared to just 15,000 applications for international protection over the same period.

In much smaller numbers, temporary protection was also granted to Russians (2,100, mainly in Spain and Germany), Nigerians (820, mainly in Portugal, Germany and Finland), Moldovans (680, mainly in Germany, Romania and Spain) and Moroccans (540, mainly in Portugal, Germany and Spain).v

While women and girls were a minority among applicants for international protection in EU+ countries, they received about three-fifths of all decisions granting temporary protection in 2023. Over one-quarter of all decisions granted temporary protection to minors (26%), practically all of whom were Ukrainian nationals.

Housing

Article 13 of the Temporary Protection Directive establishes that Member States must ensure that beneficiaries have access to suitable accommodation, social welfare, medical care, employment and education. The rapid implementation of the directive or comparable schemes across EU+ countries in early 2022 facilitated the regularisation of Ukrainian nationals’ residence under simplified procedures and their access to rights associated with the temporary protection status.181As the military aggression continued in 2023, new challenges emerged in terms of ensuring longer-term solutions for the protection and integration of displaced persons from Ukraine.

Housing continued to be a pressing topic, and accommodation programmes and allowances were extended in Bulgaria,182 Romania183 and Slovakia,184 while new structures and solutions to facilitate access to accommodation were introduced in Czechia,185 Cyprus186 and Germany.187 In Lithuania, the IOM allocated funding to partially cover the rent of beneficiaries of temporary protection.188 High occupancy rates and mounting pressure on the reception system in Norway189 led to increased requirements to access housing.190 Norway also announced enforcing additional measures in the existing integration programme (valid for all persons who receive some form for international protection) in order to support Ukrainians in finding employment rapidly to allow them to support themselves during their stay in the country.191 The Irish government amended the accommodation offering for new arrivals in December 2023.192

Employment

The labour market integration of Ukrainian nationals gained increased attention throughout 2023. National labour authorities in Finland,193 Italy,194 Romania195 and Slovakia196 published studies and statistics focused on the rate of employment and fields of work of displaced persons from Ukraine.

Beneficiaries of temporary protection are generally allowed to work without the need to obtain a separate work permit, facilitating the procedural aspects of their integration in the labour market. However, the demographic composition of displaced persons from Ukraine has posed additional challenges. Almost one-half of temporary protection beneficiaries in the EU are adult women, while children account for almost one-third.197 The burden associated with care responsibilities and the unavailability of appropriate childcare were indicated as potential restrictions to Ukrainian women’s prospects to take up employment in host countries.198

There are also indications that Ukrainians often take on lower-skilled positions.199 Lengthy procedures for the recognition of diplomas or qualifications, particularly in the fields of health and education, were cited as one of the reasons why temporary protection beneficiaries often resorted to lower-level jobs.200 In 2022, the European Commission issued a recommendation advising Member States to streamline recognition procedures for academic and professional qualifications of displaced persons from Ukraine.201 Some countries began to implement measures to update the recognition system, including by accepting qualifications on a declarative basis for non-regulated professions.202

Education

Other measures to support the social and economic integration of Ukrainian nationals were put in place throughout 2023, including in the field of education. Spain implemented scholarships to support language training of temporary protection beneficiaries in the reception system.203 In Lithuania, following announcements that displaced persons from Ukraine will be required to pass a language examination as of March 2024,204 the IOM committed to provide free language lessons.205Facilitating access to education of both children and adults became a priority in Romania206and Slovakia.207

Healthcare

Language barriers may also pose obstacles in terms of access to healthcare, which combined with pressure on health systems could restrict beneficiaries’ possibilities to effectively use medical services in the host countries. New information provision initiatives, including information on access to medical care, were launched by national authorities and the IOM in Bulgaria, Lithuania and Norway.208

With the aim of improving healthcare for beneficiaries of temporary protection in Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Slovakia, the European Commission launched a dedicated project within the EU4Health programme. Together with the IOM and the World Health Organization (WHO), the European Commission aims to reinforce the capacity of national health systems to cope with increasing inflows, improve access to public health services and extend coverage.209

While the extension of the temporary protection status until 2025 was a welcomed development, UNHCR reiterated its appeal to increase efforts to integrate people with vulnerabilities. The agency warned that obstacles to access accommodation, healthcare and employment, as well as administrative barriers to obtain documentation, may prompt vulnerable people to return to Ukraine.210Their second Position on Voluntary Return to Ukraine211urged host countries to ensure that effective mechanisms for vulnerability identification and referral are in place. In this regard, initiatives to provide information on services available to people with disabilities were launched by civil society organisations in Poland212and Slovakia.213

Efforts towards a better understanding of the needs of displaced persons from Ukraine persisted in 2023. The EUAA, together with the OECD, continued to implement the Surveys of Arriving Migrants from Ukraine (SAM-UKR) and published two fact sheets in June214and October2152023. The surveys show moderate satisfaction with support services and map urgent needs perceived by displaced persons in terms of language learning, financial support and employment. Similar surveys were launched by various stakeholders in Germany,216Lithuania,217 Poland218and Sweden.219

Information provision

National authorities, international organisations and civil society organisations continued to tailor information and web pages specifically for displaced persons, for example on registering for temporary protection, accessing the labour market and attending school.

The Directorate for Immigration (UDI) in Norway launched a “New in Norway” website targeted at newly-arrived displaced persons from Ukraine. The website is available in several languages, including English, Norwegian, Ukrainian and Russian. In addition, the Norwegian Organisation for Asylum Seekers (NOAS) launched a new website for displaced persons from Ukraine (available in Norwegian and Ukrainian). The information relates to their initial arrival, how to access services and about travel to other countries.

Likewise, the National Institute of Public Health (NIJZ), UNHCR, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the IOM published practical tips on living in Slovenia in Ukrainian.220The Legal Centre for the Protection of Human Rights and the Environment in Slovenia has been providing private consultations to Ukrainians on their rights and duties and the procedure for temporary protection.

The Federal Agency for Reception and Support Services (BBU) in Austria provides information in counselling centres about assisted humanitarian returns to a country of origin for third-country nationals who fled Ukraine. The BBU and the IOM are supporting and preparing these individuals for their onward journeys.221

- 171Eurostat. (2023, December 8). More than 4.2 million people under temporary protection.

- 172Council of the European Union. (2023, September 28). Ukrainian refugees: EU member states agree to extend temporary protection.

- iDenmark, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland are not bound by the Temporary Protection Directive but have implemented similar national protection provisions. More information can be found on Who is Who: Temporary protection for displaced persons from Ukraine

- 173European Labour Authority. (2023). Overview of the measures taken by EU and EFTA countries regarding employment and social security of displaced persons from Ukraine. Comparative summary report. https://www.ela.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-06/Report-on-the-Overview-of-the-measures-taken-by-EU-and-EFTA-countries-regarding-employment-and-social-security-of-displaced-persons-from-Ukraine.pdf

Ministry of Labour and Social Policies | Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali. (2023, December 29). Ucraina, prorogati fino al 31 dicembre 2024 i permessi di soggiorno per protezione temporanea [Ukraine, residence permits for temporary protection extended until 31 December 2024]. - iiFor more details on UNHCR’s activities in EU+ countries, see Who is Who in International Protection: UNHCR.

- 174Blue Dot Hub. Safe Space, Protection and Support Hub. (2023). Country hubs.

- 175European Union Agency for Asylum. (2023). Providing Temporary Protection to Displaced Persons from Ukraine: A Year in Review.

- 176Lais, M. (2023, April 7). VfGH: Zum vorübergehenden Aufenthaltsrecht für Staatsangehörige der Ukraine nach der Vertriebenen-Verordnung [VfGH: On the temporary right of residence for Ukrainian citizens according to the Displaced Persons Ordinance] [Blog Asyl].

- 177Finnish Immigration Service | Maahanmuuttovirasto. (2023, September 7). Temporary protection is not granted to certain third-country nationals as of 7 September 2023. https://migri.fi/-/tilapaista-suojelua-ei-myonneta-3.-maan-kansalaisille?languageId=en_US

- 178State Secretary for Justice and Security | Staatssecretaris van Justitie en Veiligheid. (2024, April 25). Tijdelijke regels over de opvang van ontheemden uit Oekraïne (Tijdelijke wet opvang ontheemden Oekraïne) [Temporary rules on the reception of displaced persons from Ukraine (Temporary Act on the Reception of Displaced Persons Ukraine)].

- 179The Ministry of Justice and Public Security | Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet. (2023, December 20). Ukrainians with dual citizenship will not be granted temporary collective protection in Norway.

- 180Ministry of Justice and Public Security | Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet. (2023, December 12). Ukrainians who travel to their country of origin risk losing their residence permit in Norway.

- iiiEurostat “Decisions granting temporary protection by citizenship, age and sex – monthly data”, data at the end of December 2023 (last update on 5 February 2024). Data for December 2023 were missing for Switzerland. [migr_asytpfm]

- ivThe number of decisions on temporary protection from March-July 2022 is underestimated because data for Germany were only available as a total number. Germany started reporting monthly data on decisions on temporary protection as of August 2022.

- vThe nationality was unknown for approximately 680 beneficiaries of temporary protection.

- 181European Union Agency for Asylum. (2023). Providing Temporary Protection to Displaced Persons from Ukraine: A Year in Review.

- 182Council of Ministers of the Republic of Bulgaria | Министрски Съвет На Република България. (2023, June 28). Програмата за хуманитарно подпомагане на украинци с временна закрила в България се удължава до края на септември [The program for humanitarian assistance to Ukrainians with temporary protection in Bulgaria is extended until the end of September].

- 183Ordonanță de Urgență nr. 22 din 12 aprilie 2023 pentru modificarea și completarea Ordonanței de urgență a Guvernului nr. 15/2022 privind acordarea de sprijin și asistență umanitară de către statul român cetățenilor străini sau apatrizilor aflați în situații deosebite, proveniți din zona conflictului armat din Ucraina [Emergency Ordinance No 22 of 12 April 2023 for the amendment and completion of the Government Emergency Ordinance No 15/2022 regarding the granting of humanitarian support and assistance by the Romanian state to foreign citizens or stateless persons in special situations, coming from the area of the armed conflict in Ukraine], April 12, 2023.

- 184European Website on Integration. (2023, June 2). Slovakia: Accommodation allowance extended for those displaced from Ukraine. https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/news/slovakia-accommodation-allowance-extended-those-displaced-ukraine_en

Ministry of the Interior | Ministerstvo vnútra. (2023, December 6). Príspevok za ubytovanie odídencov z Ukrajiny sa bude poskytovať do konca marca 2024 [Housing allowance for persons from Ukraine extended]. - 185Ministry of the Interior | Ministerstvo Vnitra. (2023, March 31). Asistenční centra pomoci Ukrajině od dubna převezme Ministerstvo vnitra [The Ministry of the Interior will take over the assistance centers to help Ukrainians from April].

- 186Deputy Ministry for Social Welfare | Υφυπουργείο Κοινωνικής Πρόνοιας. (2023, May 24). Application for the provision of a rent subsidy to displaced persons from Ukraine who have secured Temporary Protection status.

- 187Federal Ministry for the Interior | Bundesministerium für Inneres (2023, February 11). Zentrale Wohnraumvermittlung für Geflüchtete aus der Ukraine [Central housing placement for refugees from Ukraine].

- 188IOM Lithuania. (2023, September 15).

- 189Norwegian Directorate of Immigration | Utlendingsdirektoratet. (2023, August 31). Sterk økning i ankomster [Strong increase in arrivals]. https://www.udi.no/en/latest/sterk-okning-i-ankomster/

Norwegian Directorate of Immigration | Utlendingsdirektoratet. (2023, October 11). Må skaffe flere mottaksplasser og øke bosettingstakten [Must obtain more reception places and increase the rate of settlement]. - 190Ministry of Justice and Public Security | Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet. (2023, December 11). Endringer i krav til innkvarteringstilbud til asylsøkere [Changes in requirements for accommodation offers for asylum seekers].

- 191Ministry of Justice and Public Security | Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet. (2023, October 24). Lenger i mottak, raskere ut i jobb [Longer in reception, faster out to work].

- 192Department of the Taoiseach | Roinn an Taoisigh. (2023, December 12). Government approves changes to measures for those fleeing war in Ukraine. https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/b5d86-government-approves-changes-to-measures-for-those-fleeing-war-in-ukraine/

- 193Finnish Immigration Service | Maahanmuuttovirasto. (2023, June 9). The number of seasonal work permits is declining – many Ukrainians receiving temporary protection work on farms. https://migri.fi/-/kausityolupien-hakemusmaarat-laskussa-tilapaista-suojelua-saaneet-ukrainalaiset-tyoskentelevat-maatiloilla?languageId=en_US

- 194Ministry of Labour and Social Policies | Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali. (2023, July 11). L'Emergenza Ucraina e il progetto PUOI.

- 195National Employment Agency | Agentia Nationala pentru Ocuparea Fortei de Munca. (2023, September 25). Situația încadrării pe piața muncii a cetățenilor ucraineni, prin intermediul ANOFM [The employment situation of Ukrainian citizens on the labour market, through ANOFM].

- 196Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family of the Slovak Republic | Ministerstvo práce, sociálnych vecí a rodiny Slovenskej republiky. (2023, October 4). Odídenci z Ukrajiny sa na slovenskom trhu práce uplatňujú ťažšie [Expats from Ukraine find it more difficult to apply on the Slovak labour market]. https://www.employment.gov.sk/sk/uvodna-stranka/informacie-media/aktuality/odidenci-z-ukrajiny-slovenskom-trhu-prace-uplatnuju-tazsie.html

European Website on Integration. (2023, July 31). Slovakia: Continued growth in the employment and economic activity of migrants. - 197Eurostat. (2023, December 8). More than 4.2 million people under temporary protection.

- 198Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. The labour market integration challenges of Ukrainian refugee women. In Joining Forces for Gender Equality: What is Holding us Back?

- 199European Labour Authority. (2023). Overview of the measures taken by EU and EFTA countries regarding employment and social security of displaced persons from Ukraine. Comparative summary report. https://www.ela.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-06/Report-on-the-Overview-of-the-measures-taken-by-EU-and-EFTA-countries-regarding-employment-and-social-security-of-displaced-persons-from-Ukraine.pdf

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2023). Fleeing Ukraine: Implementing temporary protection at local levels. - 200European Labour Authority. (2023). Overview of the measures taken by EU and EFTA countries regarding employment and social security of displaced persons from Ukraine. Comparative summary report.

- 201European Commission (EC), Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. (2022). Recognition of qualifications for people fleeing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- 202European Labour Authority. (2023). Overview of the measures taken by EU and EFTA countries regarding employment and social security of displaced persons from Ukraine. Comparative summary report. https://www.ela.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-06/Report-on-the-Overview-of-the-measures-taken-by-EU-and-EFTA-countries-regarding-employment-and-social-security-of-displaced-persons-from-Ukraine.pdf

Lege de ratificare a Acordului între Guvernul României și Cabinetul de Miniștri al Ucrainei privind recunoașterea reciprocă a actelor de studii, 12 October 2023. - 203Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migrations | Ministerio de Inclusión, Seguridad Social y Migraciones. (2023, March 7). La Secretaría de Estado de Migraciones, Redeia y FEDELE firman un protocolo para mejorar el nivel de español de refugiados ucranianos [The Secretary of State for Migration, Redeia and FEDELE sign a protocol to improve the level of Spanish of Ukrainian refugees].

- 204Lithuanian National Radio and Television | Lietuvos nacionalinis radijas ir televizija. (2023, April 5). Lietuvių kalbos institucijos kitąmet pradės tikrinti darbuotojus iš Ukrainos [Lithuanian language authorities to start checking Ukrainian workers next year].

- 205IOM Lithuania. (2023, September 8). IOM Lietuva kviečia ukrainiečius nemokamai mokytis lietuvių kalbos [IOM Lithuania invites Ukrainians to learn the Lithuanian language for free].

- 206Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Romania. In Education at a Glance 2023.

- 207Digital coalition | Digitálna koalícia. (2023, August 1). Ukrajinský žiak [Ukrainian student]. https://ukrajinskyziak.sk/

uropean Website on Integration. (2023, August 17). Slovakia: Universities play an active role in supporting those displaced from Ukraine. - 208IOM Bulgaria. (2023, August 23). Info sessions in Plovdiv and Haskovo for refugees from Ukraine. https://bulgaria.iom.int/news/info-sessions-plovdiv-and-haskovo-refugees-ukraine

IOM Lithuania. (2023, October 23). E. Bingelis: Atidaromas naujas centras skirtas užsieniečiams [E. Bingelis: "A new centre for foreigners is opening"]. - 209European Commission, P. H. (2023, December 6). EU4Health grants €4 million to improve healthcare for Ukrainian refugees and displaced persons under temporary protection.

- 210United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2023, November 15). UNHCR warns worsening conditions and challenges facing vulnerable Ukrainian refugees in Europe. UNHCR - the UN Refugee Agency.

- 211United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (June 2023). https://www.refworld.org/docid/649a7c744

- 212Association for Legal Intervention I Stowarzyszenia Interwencji Prawnej. (2023, June 27). Informator dla osób z niepełnosprawnością, które przybyły do Polski w związku z wojną na Ukrainie [Guide for people with disabilities who came to Poland in connection with the war in Ukraine].

- 213Platform of families of children with disabilities | Platforma rodín detí so zdravotným znevýhodnením. (2023, July 4). Mapa podpory pre deti so zdravotným znevýhodnením z Ukrajiny [Map of support for children with disabilities from Ukraine].

- 214European Union Agency for Asylum. (June 2023). Surveys of Arriving Migrants from Ukraine: Thematic fact sheet.

- 215European Union Agency for Asylum. (October 2023). Surveys of Arriving Migrants from Ukraine: Thematic Factsheet - Issue 2.

- 216Federal Office for Migration and Refugees | Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. (2023, July 12). Geflüchtete aus der Ukraine: Knapp die Hälfte beabsichtigt längerfristig in Deutschland zu bleiben [Ukrainian refugees: Nearly half intend to stay longer term in Germany].

- 217IOM Lithuania. (2023, June 9). Lithuania — Surveys with Refugees from Ukraine: Needs, Intentions, and Integration Challenges (January - March 2023). https://dtm.iom.int/reports/lithuania-surveys-refugees-ukraine-needs-intentions-and-integration-challenges-january?close=true

- 218United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2023, July 5). Nowy sondaż UNHCR na temat uchodźców z Ukrainy w Polsce[New UNHCR survey on refugees from Ukraine in Poland].

- 219Swedish Migration Agency (SMA) | Migrationsverket. (2023, April 4). Enkät om situationen för personer från Ukraina [Survey on the situation of people from Ukraine].

- 220National Institute of Public Health | Nacionalni inštitut za javno zdravje. (2023). Практичні поради щодо перебування в Республіці Словенія[Practical Advice for Staying in the Republic of Slovenia].

- 221Federal Agency for Reception and Support Services | Bundesagentur für Betreuungs- und Unterstützungsleistungen. (2023). Third Country Nationals. https://www.bbu.gv.at/third-country-nationals