The Dublin system is a set of ‘criteria and mechanisms for determining which Member State is responsible for considering an application for asylum or subsidiary protection’ (Article 78 of the Treaty on the functioning of the European Union, TFEU) 131.

The system establishes the principle that only one Member State is responsible for examining an asylum application. The criteria for establishing responsibility run, in hierarchical order, from family considerations (protection of unaccompanied minors and family unity), to recent possession of visa or residence permit in a Member State, to whether the applicant has entered the common territory of the Dublin Member States irregularly coming from a third country 132.

The first objective of the system is to guarantee that a person in need of international protection has an effective access to procedures for granting international protection. This is important for avoiding ‘refugees in orbit’ situation, where no Member State would be willing to accept responsibility for examining an application. The Dublin system also aims to prevent the abuse of the asylum procedure and preclude multiple applications for asylum submitted by the same person in several Member States with the sole aim of extending their stay in the Member States.

Regulation (EU) 604/2013, commonly referred to as the Dublin III Regulation, is the cornerstone of the CEAS, aiming to provide a clear, workable and rapid method for determining the Member State responsible for the examination of an application for international protection of a third-country national or a stateless person.

The official statistics on the Dublin procedure are collected by Eurostat on an annual basis at EU+ level 133. The relevant EU Regulation 134 foresees a time limit of three months for data transmission, but challenges persist in this regard and at the time of writing the Eurostat Dublin annual statistics were still not sufficiently complete to provide for a comprehensive overview of the state of play of the Dublin system in the EU+. Therefore, the analysis presented in this chapter relies on EASO data, which are provisional and not validated, and might differ from validated data subsequently submitted to Eurostat. 135 Moreover, the conclusions made on specific points below can be considered as partial, because EASO data cover only three Dublin indicators: decisions on outgoing Dublin requests, decisions to apply the discretionary clause based on Article 17(1)136 and implemented outgoing transfers.

Decisions on Dublin requests

In the context of the present section, based on EPS data collection, decisions on Dublin requests cover all responses to requests, including implicit acceptances when a partner country fails to provide an answer within the time frame stipulated by the Regulation. In 2018, 28 EU+ countries regularly exchanged data on the decisions they received on their outgoing Dublin requests 137. The United Kingdom shared data for the period August – December 2018. The 28 EU+ countries received 138 445 decisions on their outgoing Dublin requests, and if the partial reporting by the United Kingdom is considered the number increases to 139 984. Considering the 26 EU+ countries which reported regularly in both 2017 and 2018, the overall number of decisions on Dublin requests declined by approximately 5 %. The value of this indicator is more meaningful when considered in relation to asylum applications lodged. In 2018, the ratio of received Dublin decisions to asylum applications was 23 %. This pattern was similar to 2017 but the ratio actually increased slightly 138. This may imply that a high number of applicants for international protection continued to pursue secondary movements in the EU+ countries.

Germany and France received most of the decisions on Dublin requests, accounting for 37 % and 29 % respectively. While Germany received slightly fewer decisions than in 2017, the number of decisions taken on French requests increased proportionally to the overall number of requests. Other countries receiving high numbers of responses in 2018 included the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, Italy, Switzerland and Greece. Among them, Austria and Greece received considerably fewer decisions than in 2017, whereas an increase took place for decisions on Italian requests.

Almost one in three decisions were taken by Italy and almost one in six by Germany in 2018. Other important partner countries included Spain, Greece, France, Sweden, and Austria. The most important changes compared to 2017 included a significant increase in the Dublin decisions issued by Greece and Spain. At the same time, there was a reduction in the number of cases in which the discretionary clause was used vis-à-vis Greece (read more below). However, this decrease was very small compared to the increase in Greek decisions. Furthermore, Bulgaria, Hungary and Germany responded to considerably fewer requests than in 2017.

Acceptance rates

The overall acceptance rate for decisions on Dublin requests in 2018 was 67 %, down by 8 percentage points from 2017. Variation in acceptance rates continued to exist across countries. For example, there were very high proportions of positive responses coming from Portugal, the Czechia and Italy, and considerably low proportions from Greece, Hungary and Bulgaria. It is important to note that the overall decrease in the acceptance rate at the EU+ level was driven by decreases in several partner countries with diverse rates.

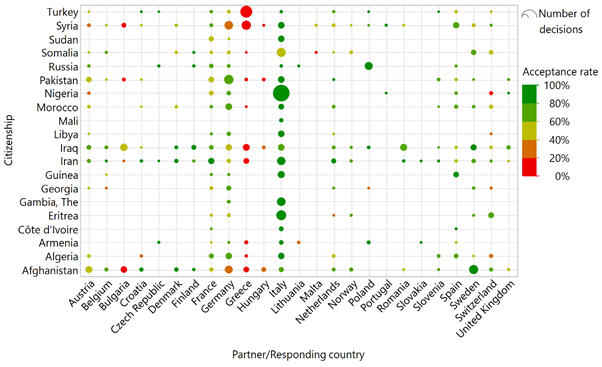

Most Dublin decisions in 2018 concerned citizens of Afghanistan (9 % of the total), Nigeria (8 %), Iraq (6 %) and Syria (6 %) . 139 These were the same top citizenships as in 2017, albeit in a different order. There were considerably fewer Dublin decisions on cases of Syrians, Afghans and Iraqis in 2018. In contrast, there was a sizable increase in the number of decisions taken regarding citizens of Turkey and Nigeria, and to a lesser extent Iran and Pakistan. Figure 27 presents the acceptance rates of the partner countries for each of the top 20 citizenships. The estimates are based on data exchanged by 28 EU+ reporting countries. 140 The size of the bubbles corresponds to the total number of decisions on Dublin requests.141 The colour of the bubble indicates the acceptance rate (green = high, red = low). Similar to 2017, in most cases the responding countries followed a relatively consistent pattern of responses irrespective of citizenship.

| Numbers of decisions reached in response to Dublin requests (size of circle) and acceptance rates (green = high, red = low), by partner country and top 20 citizenships

|

|

|

Figure 27: Partner countries generally had systematic acceptance rates, independent of the citizenships |

EASO data do not contain information on the specific article of the Dublin Regulation used as a basis for sending a request. However, it is possible to distinguish between responses to take-back 142 and take-charge requests. 143 This information was reported for 71 % of the decisions in 2018. 144 Among those decisions with reported legal basis, about two-thirds were in response to take-back requests. This implies that most of the decisions were related to cases in which applications had already been lodged in another EU+ country. The acceptance rate for take-back requests (65 %) was almost the same as that of take-charge requests (64 %) but due to the high number of decisions with unknown legal basis the values should be interpreted with care.

Click on the links below to navigate through the content

| Discretionary clause |

Article 17(1) of the Dublin Regulation, known as the discretionary or sovereignty clause, was invoked over 12 300 times in 2018,145 in almost two-thirds of the cases the clause was applied by Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Switzerland also made common use of the discretionary clause. Two-fifths of the cases in which Article 17(1) was invoked identified Italy as the partner country to which a request could have been sent, 22 % identified Greece and 9 % Hungary. Almost one-fifth of the decisions to apply the discretionary clause the potential partner country was not reported and the same was true for the citizenship of the persons concerned. Article 17(1) was invoked most commonly for nationals of Nigeria (20 %), Turkey (12 %), Syria (10 %), Iraq (7 %), and Afghanistan (6 %) in 2018. Compared to 2017, the discretionary clause was used more often for cases of Nigerian and Turkish citizens, and less often for Pakistanis and Afghans.

As was the case in 2017, among the EU+ countries that reported both on decisions on Dublin requests and use of the sovereignty clause, overall for every decision to apply Article 17(1), eight Dublin transfer requests were accepted by the partner countries. This implies that EU+ countries more often decided to send out requests rather than to invoke the discretionary clause and thereby assume responsibility themselves.

| Transfers |

In 2018, the reporting countries implemented over 28 000 transfers. 146 Considering the 26 EU+ countries which reported regularly in both 2017 and 2018, the overall number of implemented transfers increased by approximately 5 %. Almost one-third of the transfers in 2018 were carried out by Germany, considerably more than a year earlier. Greece and France also implemented high numbers of transfers, and both registered increases from 2017. Conversely, fewer transfers were carried out by Austria due to the decreasing number of Dublin cases. More than half of the transferees went to Germany and Italy. Other countries receiving significant numbers of transfers included France, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Spain and Switzerland.

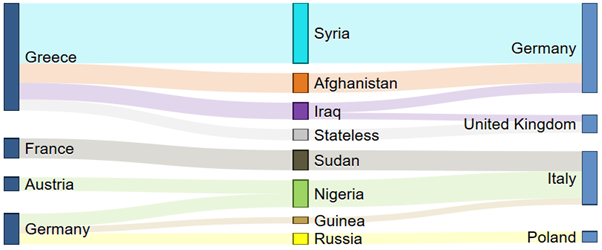

The persons transferred in 2018 continued to represent a diverse set of countries of origin, but half were citizens of Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria, Sudan, Russia and Iran. Compared to 2017, there were notably more transfers of Sudanese, Iraqis, stateless, Afghans and Iranians but fewer transfers of Syrians. Figure 28 illustrates the 10 largest combinations of sending country, citizenship and receiving country for implemented transfers. Similar to 2017, the top combination involved Syrian nationals transferred from Greece to Germany, and represented 8 % of all implemented transfers. The other major flows comprised Sudanese sent from France to Italy and Afghans sent from Greece to Germany. The top ten flows continued to feature a diverse sent of transferees in terms of citizenships: three Asian, three African, one European and stateless persons.

|

Top 10 combinations of sending country (left), citizenship (middle) and receiving country (right) for implemented Dublin transfers |

|

|

Figure 28: The top 10 flows represented 23 % of all transferees |

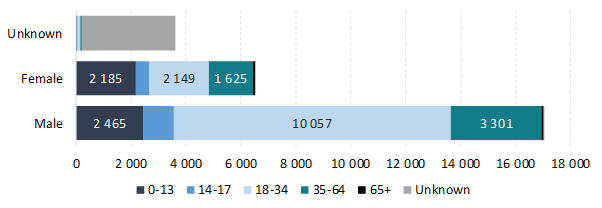

Almost two-thirds of the persons transferred were adults, almost one-quarter were minors and for the remaining 12 % the age group was not reported. There were almost three times more male than female transferees. Overall, the patterns for age and sex were very much in line with 2017. The number of male and female minors remained remarkably similar, potentially implying that minors in Dublin transfers were largely involved in asylum applications with their families. 147

|

Sex and age groups of Dublin transferees |

|

|

Figure 29: At least half of the transferees were adult males |

In general, main developments in EU+ countries with regard to Dublin procedure reflected the volume of cases that needed to be processed. While this section focuses on general Dublin procedures, information regarding application of detention under the Dublin III Regulation is presented in the section on Detention.

| Organisational changes |

Several EU+ countries introduced relatively substantial organisational changes.

Further to important changes in organisational framework in 2017 introduced by Germany, throughout 2018 responsibilities within the Dublin Group, which is responsible for handling the Dublin procedure, have been re-organised.148 In France, in view of ensuring higher convergence across the country, it was decided that the Dublin procedure would be carried out by one prefecture (Pôles Régionaux Dublin - PRD) per region. This led to creation of 11 specialised Dublin Units (being fully operational as of 1 January 2019), which replaced close to 100 prefectures which were responsible for implementing the Dublin Regulation.

According to civil society, this regionalisation process created difficulties for asylum seekers who found it cumbersome to travel to the competent prefecture after having received transfer decision notice. As a consequence, missing an appointment at the Dublin Unit led to reception conditions being withdrawn and applicants becoming exposed to destitution.

Switzerland was preparing to introduce operational changes as an outcome of which the Dublin-Out procedures will be decentralised into different regions by 1 March 2019. Similar discussions were underway in the UK concerning the Third Country/Dublin Unit that makes requests to other Dublin partners.

In Austria it was primarily due to the increasing number of incoming requests. As a result, a certain percentage of the Dublin-In caseload started to be handled in the Initial Reception Centres which are normally only responsible for the Dublin-Out procedure.

In Malta, following the preparations in 2017, the operational part of the Dublin Regulation has now entirely shifted from the Immigration Police to the newly set up Dublin Unit within the Office of the Refugee Commissioner.

Slovenia reported that the national Dublin and Eurodac contact points started operating under the same organisational unit, which contributed to swifter acquisition of information on possible Eurodac hits and eventually to faster identification of potential Dublin cases.

As far as legislative developments are concerned, according to the Article 11 of the new Law 132/2018, Italian prefectures may establish a maximum of three Dublin Unit’s territorial offices, in order to overcome the secondary movements of asylum seekers.

At the operational level, to support the Irish Naturalisation and Immigration Service and the International Protection Office (IPO) in the reduction of caseloads, Ireland further increased the staffing by recruiting additional panel members of the Case Processing Panel of Legal Graduates, who inter alia support the IPO in processing cases and represent the IPO at appeal hearings in respect of transfer decisions at the International Protection Appeals Tribunal. 149 In addition, various operational changes have been made in the IPO with a view to expedite the process and reduce processing times. Belgium reported that its Dublin Unit faced staff challenges.

| Assessment of the best interest of a child |

Major developments can be also noted with regard to assessment of the best interest of a child in the context of Dublin procedure.

Since 2018, the UAM’s Unit of the Belgium Immigration Office also conducts interviews with adult family members in the context of Article 8 of the Dublin III Regulation to ensure that the best interest of the minor is taken into account. Based on their advice, the Dublin Unit of the Immigration Office decides if a reunification of the child with the adult involved is indeed in his or her best interest.

In Greece, according to the adopted amendment (L4554/2018), a new tool for the best interest assessment for UAMs was introduced in the Dublin procedure. This tool aims at collecting and evaluating all the required information to facilitate processing such requests under the Dublin III Regulation. 150 The new provisions improved also the quality of the Dublin processes and the provision of Dublin-related information.

| Transfers to Greece |

As for transfers to Greece, as a continued trend going into 2018, Romania and Malta resumed sending requests to Greece in accordance with the Dublin III Regulation and Commission recommendation C (2016) 8525.151

21 EU+ countries had resumed requesting Greece to take charge of/take back applicants by December 2018: these are Ireland, Belgium, Switzerland, the Czechia, Finland, Germany, Cyprus, Croatia, Hungary, Luxembourg, Lithuania, Latvia, Norway, Poland, Romania, Sweden, Slovenia, Slovakia, Estonia, the Netherlands and Malta. This resulted in higher number of Greek decisions on Dublin requests. However, the increase was largely reflected in rejections of requests. According to the Greek Asylum Service, Greece accepted 232 requests (compared to 75 in 2017), but there were only 23 transfers made to Greece.152

The Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security instructed the Directorate of Immigration (UDI) on 28 November 2018 to assess whether the Dublin procedure can be applied in cases where the applicant is an unaccompanied minor who has previously been in Greece and when a family member of the unaccompanied minor is legally present there, provided that it is in the best interests of the minor. Further, the instruction states that requests from Greek authorities to take charge of a family member of a minor who has previously been in Greece with his or her family shall be declined. This was mainly to discourage families to send their children alone and irregularly around in Europe, in order for the family to follow later on.

On 28 March 2018, the Immigration Appeals’ Board in Norway issued the first decision on its merits regarding a transfer to Greece under the Dublin Regulation. The Board upheld the UDI's decision. After a thorough assessment of the claims, the Board reached the overall conclusion that the general situation for asylum seekers in terms of the asylum procedure as such including the reception centres has improved since the M.S.S. judgement and that in the individual case there is no indication that a transfer to Greece would breach Article 3 ECHR.

| Administrative arrangements in the Dublin procedure |

Among administrative changes in the Dublin procedure reported by EU+ countries, most of them concerned the time frames implemented for different actions. More specifically, Denmark changed timeline for issuing transfer decisions. Transfer decisions are therefore issued only after receipt of acceptance as opposed to the previous set up according to which decisions were issued straight after the personal interview (before the request for take-back or take-charge was sent).

The Directorate of Immigration in Norway has thoroughly assessed the CJEU Grand Chamber judgment in X, X v. the Netherlands (C-47/17 and C-48/17) on the interpretation of the Implementing Regulation to of the Dublin III Regulation. Guidelines for the practice regarding deadlines for re-examinations have not yet been issued.

On 1 August 2018, the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees introduced a new procedure regarding church asylum, within the context of religious institutions offering temporary sanctuary to persons whose cases concern transfers under the Dublin III Regulation. Asylum seekers entering church asylum are considered to be absconded within the meaning of Article Article 29(2) of the Dublin III Regulation.153 These measures have triggered an extensive debate, and many religious and civil society organisations voiced their concerns.154

| Bilateral agreements |

In order to expedite Dublin procedures and enhance transfer options, Germany also concluded two bilateral arrangements pursuant to Article 36 Dublin III Regulation with both Portugal and France. The bilateral agreement with Luxembourg was concluded in March 2019.

Germany also concluded relevant bilateral arrangements with Greece and Spain outside the Dublin III Regulation. Application of the procedures makes it possible to refuse entry to third–country nationals who request protection with the Federal Police after being apprehended at the German-Austrian land border (except for unaccompanied minors) and transfer them to the Member State where they have already applied for protection (generally within a period of no more than 48 hours). In return, Germany pledged to speed up the process of family reunification by the end of 2018. These bilateral arrangements have been presented by Germany as an interim response to the political deadlock preventing the adoption of the CEAS reform. In its Policy Paper, ECRE voiced criticism over these specific bilateral agreements, stating that some of them bypass the rules set out in the Dublin system with the aim of quickly carrying out transfers.155

In October 2018, the Portuguese authorities announced a bilateral agreement with Greece to implement a pilot relocation process for 100 asylum seekers from Greece to Portugal. 156

| Transfers to Hungary |

Similarly to 2016 and 2017, in 2018, the suspension of Dublin transfers to Hungary was also noted. On 22 March 2018, the State Secretary for Justice and Security in the Netherlands decided to formally suspend the sending of take-back and take-charge requests to Hungary in the context of the Dublin III Regulation. The Netherlands stopped implementing transfers to Hungary following a decision of the Dutch Council of State on 26 November 2015 157 as well as questions about the compatibility of new Hungarian asylum legislation with European law, but requests were still being sent. Subsequently the Netherlands attempted to carry out a conciliation procedure with Hungary, but Hungary rejected the offer and, in return, the State Secretary of the Netherlands took a decision to suspend the sending of requests.158

| Transfers to Italy |

As a result of recent changes in the asylum law introduced by Italy, a new circular letter of 8 January 2019 was sent from the Italian Dublin Unit to all Member States indicating that families will no longer be placed in SPRAR centres but in first reception centres and emergency reception centres.159

In conjunction with the ruling of the Danish Refugee Appeals Board from 21 November 2018, the Danish Immigration Service initiated a hearing regarding the accommodation facilities in Italy via the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Royal Danish Embassy in Rome.

Responding to related criticism by a Luxembourgish NGO, the Minister for Immigration and Asylum noted that Luxembourg does not carry out systematic transfers to Italy but bases its decision on a case-by-case analysis.160

| Appeal/judicial review of decision on transfer |

A number of developments were also noted in regard to appeals against transfer decision. According to legislative changes introduced in France, the deadline to appeal a Dublin transfer decision was extended by 7 to 15 days. Sweden implemented in the national law Article 27.3.c of the Dublin Regulation regarding the suspensive effect of a transfer decision, while the coalition parties of the new government in Luxembourg agreed in their coalition programme to modify existing legislation regarding appeals in the context of the Dublin procedure: the appeal against a Dublin transfer decision is planned to have suspensive effect.161 These modifications also aim to increase effectiveness, especially with regard to involvement of magistrates of the First Instance Administrative Court when deciding on provisional measures to suspend transfers.162

| Practical arrangements |

EU+ countries reported also important developments that had an impact on practical arrangements with regard to implementation of transfers in the context of the Dublin procedure. During winter months, Greece encountered significant administrative difficulties in obtaining the clearance from the security police authorities and airliners when trying to organise the transfer to other countries that accepted the take-charge request using transit flight (for destinations that no direct flights are available i.e. Oslo, Malta).

The Maltese Dublin Unit has been encountering challenges with regard to Dublin requests and replies sent to Italy via DubliNet which affected the operations of the Unit (unreadable attachments; long list of outgoing Dublin information requests which are pending a reply).

The UK has observed a new phenomenon where applicants raise claims to be victims of human trafficking shortly before the date of removal. This triggers a procedure under UK national law to examine the claim, meaning that the removal cannot proceed at that time. Further analysis is needed to draw any firm conclusions, but it is a possibility that there is a tactical element to the claims being raised at a very late stage before the removal is to take place.

Following the UK/France Summit in January 2018 and the agreement of the Sandhurst Treaty that concerns cooperation on issues at the shared border, a UK Liaison Officer was posted to Paris.

| Dublin Interview |

Internal guidelines were produced to improve the quality of the personal interview in Dublin cases in Sweden. The guidelines describe what the interviewer must have in mind when conducting a personal interview. Along the same lines, Luxembourg extended the list of questions asked during the Dublin interview in order to include specific questions about the applicant’s journey to the country.

| Vulnerable applicants |

There were several important developments vis-à-vis vulnerable applicants with a view of ensuring that the correct identification of their special needs takes place as well as adequate support is granted.

In May, the revision of the Family and Friends Care Statutory Guidance for local authorities was published for public consultation by the UK Department for Education. This guidance sets out a framework for the provision of support to family and friend carers and includes revisions made to include asylum-seeking children being brought to the UK under the Dublin III Regulation to join family or relatives. 163 It was particularly relevant as in 2018 the UK continued to receive an increased number of requests to take charge of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children and other applicants on family and dependency grounds.

Greece changed its practice with regard to outgoing take-charge requests based on the family provisions or the humanitarian clause. As a result of this, the Dublin Unit no longer sends outgoing requests in cases where a subsequent separation of the family took place after their asylum application in Greece (so-called self-inflicted family separations), arguing that this is not in the best interests of the child.164

| Efficiency in processing application, including technical issues |

On 6 March 2018, the new domestic legislation European Union (Dublin System) Regulations 2018 165 came into effect in Ireland, which gave further effect to the Dublin III Regulation with the intention of making it more practical to take transfer decisions. As a result, it was anticipated that the volume of transfers from Ireland to other Member States should increase over the coming months. Between January 2017 and March 2018, there were on average fewer than 30 decisions on Irish Dublin requests. The number began increasing since April 2018, following the introduction of the new legislation, from around 50 to 251 at the end of the year.

As a significant part of the group of asylum seekers causing nuisance at Dutch reception centres often has a Dublin designation (including unaccompanied minor returnees over the age of 16), the Dutch Minister for Migration announced expanding the capacity of the Dutch Immigration and Naturalization Service (IND) in view of speeding up the Dublin procedure. 166

Estonia started introducing developments to DubliNet and the Registry of granting international protection in order to make the procedures faster and swifter mainly through a further automation of application process. The project is estimated to be finalised by 2020.

In 2018, the Dublin Unit in Slovakia successfully migrated to new DubliNet domains using electronic communications under the EU-LISA instructions and timeframes including installation of new certificates.

| Application of Dublin criteria |

Civil society reported the positive changes at the Hungarian Dublin Unit regarding wider application of Article 19(2) of the Dublin III Regulation with regard to Bulgaria in cases of asylum seekers who have waited more than three months in Serbia before being admitted to the transit zone. Before 2018, the Hungarian authorities refused to apply the article arguing that cease of responsibility of Bulgaria can only be invoked by Bulgarian Dublin Unit.

Concerns regarding the application of Dublin-related provisions expressed by civil society

Civil society raised some concerns regarding the Dublin procedures in 2018, including:

|

ECRE published a policy note in November 2018 which analyses the obstacles to the application of Dublin created by policy choices, focusing in particular on divergent decision-making outcomes and hostile political discourse and measures on migration. One area where policy choices on the application of Dublin come into tension with human rights law relates to onward deportation. Since 2017, a fresh body of case law has emerged on the suspension of Dublin transfers to Member States where an asylum seeker would unfairly be denied international protection and would face removal to his or her country of origin. Such suspensions on account of indirect refoulement have been most prominent vis-à-vis applicants from Afghanistan, due to human rights risks stemming from their unduly strict policy on granting protection to Afghan claims. 176 ECRE also published a new legal note focusing on the key provisions of the reform of the Dublin system, underlining some of the implications on applicants’ human rights and on the efficiency of the system. 177

National jurisprudence

In terms of national case law on matters relevant to the Dublin procedure, the judgements delivered in 2018 predominantly touched upon the following thematic areas: suspension of transfers, calculation of timelines and extension of deadlines, procedural consequences of transfers, application of discretionary clauses, and access to reception conditions.

In terms of procedural consequences of transfer, the Austrian Supreme Administrative Court (VwGH 3 July 2018, Ra 2018/21/0025) 178 held that the application for international protection lodged in another Member State by a Dublin returnee who already received a final negative decision in Austria (take-back case in accordance with Article 18(1)d)) is ‘automatically’ taken over by the Austrian authorities and needs to be processed upon arrival in Austria. The applicant does not need to explicitly make an application again.

The Supreme Administrative Court also ruled, in accordance with Article 13(1) of the Dublin III Regulation, that the Member State whose border an individual applying for international protection had crossed irregularly is responsible for examining that application. The court furthermore ruled that this rule applied even if the individual did not apply for international protection in that Member State but instead submitted the application later in another Member State after brief voluntary travel to a third country. The Member State’s responsibility as defined in Article 13(1) of the Dublin III Regulation did not cease even if the person concerned departs briefly from EU territory, the court held. 179

In two judgments issued on 8 May 2018 by the united chambers of the CALL in Belgium 180, the CALL ruled that an implicit decision by the Immigration Office in the context of the Dublin III Regulation to extend the transfer period from 6 months to 18 months is a disputable administrative legal act. Such a decision must be motivated and be written so that effective judicial review is possible. The Immigration Office lodged an appeal with the Council of State to contest this interpretation of the CALL. 181

On 1 October 2018, the Belgian Council on Alien Law Litigation ordered the suspension of the transfer of a Cameroonian national to Greece under the Dublin Regulation. The Cameroonian national lodged an application for international protection in Belgium in August 2018. However, Eurodac checks revealed that the applicant had first arrived in Greece, which promptly accepted the take-back request. The applicant appealed the decision using a procedure of extreme urgency in order to suspend the transfer, claiming that her vulnerable state as a victim of gender-based violence would be exacerbated in Greece. The Council accepted the urgent character of the action and proceeded to assess the serious grounds and risk of harm that would justify the suspension, eventually annulling the transfer. In this assessment, the applicant’s vulnerability was deemed crucial, especially in light of previous incidents and the lack of adequate response mechanisms to protect victims of gender-based violence in Greece. 182

The Finnish Supreme Administrative Court decision on 11 June 2018 (ECLI:FI:KHO:2018:87) 183 changed the jurisprudence set by Supreme Administrative Court previously in decisions in 2015 and 2012. The legal question concerned a situation in which the applicant (a third-country national) claimed asylum based on events that had happened in another EU MS in which the applicant had lived and towards which the Dublin Regulation was applicable. In the specific case, a Nigerian national claimed she was in danger of persecution and serious harm in Spain due to her ex-husband. According to the judgment this kind of grounds for application does not mean that the application could not be subject to the Dublin Regulation. However, if the applicant claims asylum based on events that happened in the MS responsible, they need to be assessed in accordance of ECHR Article 3. In the current case no risk of non-refoulement was found if the person would be transferred into Spain.

In its judgment of 27 August 2018 the Conseil d’Etat in France 184 stated that when the administration has completed all the procedures with its obligations under a controlled transfer and that the applicant, even though he had complied with the terms of his house arrest and was present several times in the prefecture during this period of summons, refused to board a flight in which a place was reserved for him, this refusal to embark must be regarded as an intentional subtraction to the implementation of his transfer, and consequently the person concerned must be considered to have absconded in the meaning of the Dublin Regulation.

The Superior Court of Madrid (TSJ, Tribunal Superior de Justicia de Madrid) condemned the Spanish Government for denying reception to asylum seekers transferred to Spain under the Dublin procedure. 185

In relation to asylum seekers subject to Dublin procedures, the Supreme Court in Slovenia clarified in 2018 that asylum seekers retain the right to reception conditions until the moment of their actual transfer to another Member State, despite the wording of Article 78(2) IPA. The Court stated that, to ensure an interpretation compatible with the recast Reception Conditions Directive and Article 1 of the EU Charter, Article 78(2) should not apply in Dublin cases. 186

On 7 June 2018, the Federal Administrative Court in Switzerland ruled 187, in a case concerning a provisional negative reply by the requested MS and an acceptance nearly eight months later, that an acceptance after the transfer time limit of six months (counting from the first negative reply) does not have a valid effect. According to the Court, Switzerland has become responsible for the asylum procedure in the case concerned when the transfer time limit of six months, starting with the first negative reply, ended.

The Upper Tribunal in the UK detailed in the case of MS the state’s duty to ‘act reasonably’ and to take ‘reasonable steps’ in discharging the duty to investigate the basis of a ‘take charge’ request sent by another country. This includes the option of DNA testing in the sending country or, if not, in the UK. 188

As regards the processing of requests under Article 17(2), the Upper Tribunal held in HA that there is a wide discretion available to the country receiving a ‘humanitarian clause’ request under Article 17(2), but it is not untrammelled. It was therefore for the Home Office to take into account Article 7 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, Article 8 of the ECHR and the best interest of the child when assessing whether a humanitarian clause request should be accepted. 189 190

The Council of Alien Law Litigation (CALL) in Belgium annulled different Dublin transfers, as they did not take the necessary individualised guarantees of the asylum seeker into account and therefore violated Article 3 of the ECHR. This included inter alia annulling the transfer to Spain of an asylum seeker with a newborn child,191 a transfer to Germany of an asylum seeker having diabetes and Parkinson’s disease 192 , a transfer of an asylum seeker living with HIV193 , a transfer of two young children who were accompanied by their parents194 , and a transfer of a single women due to her vulnerability as victim of sexual assault.195 196

In 2018, the courts in some Dublin states have continued to rule suspension of Dublin transfers to Bulgaria with respect to certain categories of asylum seekers due to poor material conditions and lack of proper safeguards for the rights of the individuals concerned. More information is available on AIDA – Asylum Information Database.197

Moreover, in 2018, some transfers to Italy have been halted by the national courts on account of the government’s decisions to forbid search and rescue boats from disembarking in Italian ports, its plans to limit funding for asylum seekers, and the increase in incidents of racist violence. 198

_________

131 The Dublin system is currently implemented by twenty-eight EU Member States and four associated countries (Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and Liechtenstein).

132 A hierarchy of responsibility criteria is laid down in Chapter III of the Dublin III Regulation. The criteria must be applied in order in which they are set out in the chapter. This means that a higher article number (e.g. Article 9) cannot be applied if a lower article number is already applicable (e.g. Article 8).

133 Based on Article 4.4 of the Migration Statistics Regulation, (EC) 862/2007.

134 Migration Statistics Regulation, (EC) 862/2007.

135 Iceland and Liechtenstein do not participate in EASO data exchange.

136 Through the discretionary clauses, the Dublin system makes it possible for the Member States to derogate from the application of the responsibility criteria. The first one is the ‘sovereignty clause’ in Article 17(1) of Dublin III Regulation. This clause authorises any Member State with which an application for international protection is lodged to examine it, by derogation from the responsibility criteria and/or the readmission rules; the second one is the ‘humanitarian clause’ in Article 17(2) of the Dublin III Regulation. This clause authorises and encourages Member States to bring family relations together in cases where the strict application of the criteria would keep them apart.

137 In addition to Iceland and Liechtenstein, data are not available for Belgium and Cyprus. France generally provides data with a one-month delay. Thus, data for France for 2018 actually covers the period December 2017 – November 2018.

138 However, in 2017 Dublin decisions data were missing for some countries.

139 For about 9 % of all cases the citizenship was not recorded.

140 France is generally unable to indicate the citizenship of the third-country national in the cases when its request has been rejected by the partner country. Since including these data in the overall calculation would significantly bias acceptance rates, the French reporting is not considered.

141 Combinations of partner countries and citizenships with less than 50 decisions are not shown because small samples could bias the interpretation of the results.

142 Take back requests comprise all Dublin transfer requests to take responsibility for an applicant who applied for international protection in the partner country, in accordance with Articles 18(1)b-d and 20(5) of Dublin III Regulation. More specifically, this refers to situations in which Member State A (reporting country) requests Member State B (partner country) to take responsibility for an applicant because:

- the person has already previously made an application for international protection in Member State B (and afterwards he/she has left that Member State); or

- Member State B has already previously accepted its responsibility following a take charge request from some other Member State

143 Take charge requests comprise all Dublin requests to take responsibility for an application for international protection lodged by a person who applied for international protection in the reporting country and not in the partner country, in accordance with Articles 8-16 and 17(2) of the Dublin III Regulation. More specifically, Member State A (reporting country) requests in such a case Member State B (partner country) to take responsibility for an application for international protection although the applicant in question has not submitted an application in Member State B (partner country) previously, but where the Dublin criteria indicate that Member State B (partner country) is responsible. These indications include e.g. family unity reasons (including specific criteria for unaccompanied minors), documentation (e.g. visas / residence permits), and entry (e.g. using Eurodac proof) or stay reasons and humanitarian reasons.

144 The legal basis was not reported for all decisions received by France, two decisions received by the United Kingdom and one by Greece.

145 Data on the use of the discretionary clause were shared by 27 reporting countries but eight of them did not report every month. In addition to Iceland and Lichtenstein, data for 2018 were completely missing for Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Greece.

146 The reporting countries on this indicator are generally the same as for decisions on Dublin requests. Hence, data were missing Cyprus, as well as for the period up to July for the United Kingdom. Additionally, a single month of data was missing for Finland.

147 This proposition is further supported by the fact that Dublin Member States generally do not transfer UAMs.

148 As of 1 February 2018, responsibility for incoming requests as well as coordinating transfers shifted to a different unit within the Dublin Group.

149 Irish International Protection Office (IPO), Case processing panel: recruitment of additional members.

150 Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Migration Policy, Evaluation Form for Best Child Interest - New tool for family reunification requests for unaccompanied minors (in Greek).

151 Commission Recommendation (EU) 2016/2256.

152 Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Migration Policy, Statistical Data of the Greek Dublin Unit (7.6.2013 - 31.12.2018).

153 For more information: BAMF, Note on "Church Asylum" with regard to Dublin procedures (in German).

154 See for example: asyl.net, Note regarding tightened policies and practice for church asylum (in German).

155 ECRE, Bilateral agreements: implementing or bypassing the Dublin Regulation?

156 AIDA, Country Report Portugal, 2018 Update.

157 ECLI:NL:RVS:2015:3663.

158 Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal, Brief van de Staatssecretaris van Justitie en Veiligheid aan de Voorzitter van de Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal, Nr 2374.

159 AIDA, Country Report Italy, 2018 Update.

160 Government of Luxembourg, Reaction of the Minister for Immigration and Asylum, Jean Asselborn, following the recent cocnerns expressed relating to Dublin transfers to Italy (in French).

161 UNHCR, Input to the EASO Annual Report 2018; DP, LSAP and déi gréng, Accord de coalition 2018-2023 (in French), p. 230.

162 DP, LSAP and déi gréng, Accord de coalition 2018-2023 (in French), p. 230.

163 EMN, EMN 23th Bulletin.

164 AIDA, Country Report Greece, 2018 Update.

165 IE LEG 02: European Union (Dublin System) Regulations 2018. The Regulations gave further effect to Regulation (EU) 604/2013 (the Dublin III Regulation) in Ireland and revoked the previous European Union (Dublin System) Regulations 2014 (S.I. No 525 of 2014) and the European Union (Dublin System) (Amendment) Regulations 2016 (S.I. No 140 of 2016).

166 EMN, EMN 23th Bulletin.

167AIDA, Country Report Spain, 2018 Update.

168 See for example: ECLI: ES:TSJM:2018:13292; ES:TSJM:2018:12520.

169 Fundación Cepaim, Input to the EASO Annual Report 2018.

170 UNHCR, Input to the EASO Annual Report 2018.

171 Asylex, Switzerland, Input to the EASO Annual Report 2018

172 AIDA, Country Report Malta, 2018 Update. The Maltese authorities replied to the specific information request of the civil society organisation Aditus that no transfers involving family cases were implemented to Italy throughout 2018.

173 Asylex, Switzerland, Input to the EASO Annual Report 2018.

174 Asylex, Switzerland, Input to the EASO Annual Report 2018

175 Network for Children’s Rights, Input to the EASO Annual Report 2018.

176 ECRE, To Dublin or not to Dublin?

177 ECRE, Beyond solidarity: Rights and reform of Dublin.

178 ECLI:AT:VWGH:2018:RA2018210025.L00.

179 ECLI:AT:VWGH:2018:RA2017190169.L09.

180 BE CALL, Decision no. 203 684 and BE CALL, Decision no. 203 685.

181 The CJEU delivered a relevant judgement, C-163/17, which will have an impact on the outcome of this appeal.

182 BE CALL, Decision no. 210 384.

183 ECLI:FI:KHO:2018:87.

184 ECLI:FR:CEORD:2018:423267.20180827.

185 See for example: ECLI: ES:TSJM:2018:13292; ES:TSJM:2018:12520.

186 ECLI:SI:VRS:2018:I.UP.10.2018.

187 ECLI:CE:ECHR:2018:0515DEC006798116.

188 UK Upper Tribunal, [2017] UKUT 9682.

189 UK Upper Tribunal, UKUT 00297 (IAC).

190 AIDA, Country Report United Kingdom, 2018 Update.

191 BE CALL, Decision no. 203 865.

192 BE CALL, Decision no. 207 355.

193 BE CALL, Decision no. 201 167.

194 BE CALL, Decision no. 203 861.

195 BE CALL, Decision no. 210 384.

196 AIDA, Country Report Belgium, 2018 Update.

197 AIDA, Country Report Bulgaria 2018 Update

198 ECRE, To Dublin or not to Dublin?