Under the Dublin procedure, a transfer occurs when one Member State (partner country) accepts to take responsibility for an application for international protection from another Member State (reporting country) in line with the conditions set out in the Dublin III Regulation.

Under the Dublin procedure, a transfer occurs when one Member State (partner country) accepts to take responsibility for an application for international protection from another Member State (reporting country) in line with the conditions set out in the Dublin III Regulation.

The COVID-19 pandemic and emergency measures implemented by EU+ countries made Dublin transfers difficult. Overall, about 13,600 transfers were completed, representing one-half the number of transfers in 2019.xxiii Over different periods of the year, most Member States were either not executing or receiving any transfers at all, or only carrying out and accepting a limited number of transfers. Transfer implementation was particularly affected by travel restrictions inside the EU, reduced availability of air travel options and specific requirements, such as the need for a PCR test pre-transfer or upon arrival, quarantine upon arrival, etc.

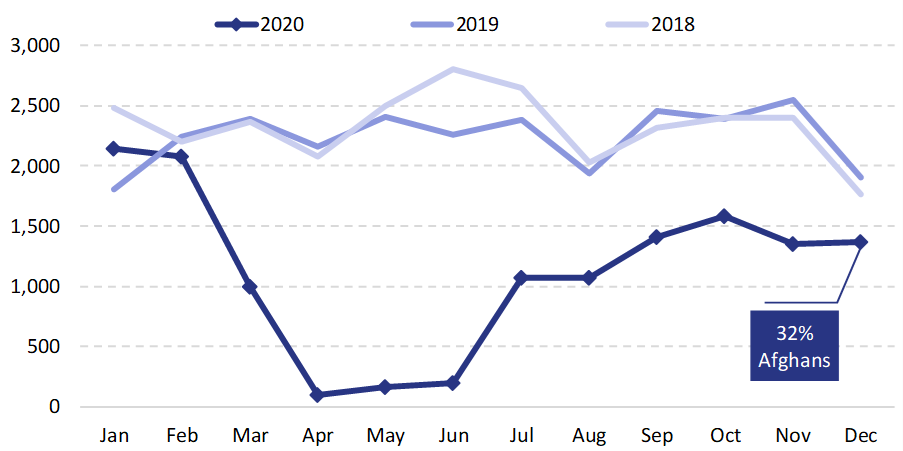

The number of transfers decreased in March 2020 and then dropped to even lower levels from April to June 2020 (see Figure 4.8). As of July 2020, the implementation of transfers gradually started to rise, but the monthly number of transfers did not return to pre-COVID-19 levels later in the year (e.g. when compared to the same months in 2019). The decline in both accepted requests and transfers in 2020 resulted in a lower ratio of implemented transfers to accepted requests (one to four).xxiv

|

Considerable decline in Dublin transfers since March 2020 |

Figure 4.8: Implemented Dublin transfers, by month, January 2018-December 2020

Source: EASO.

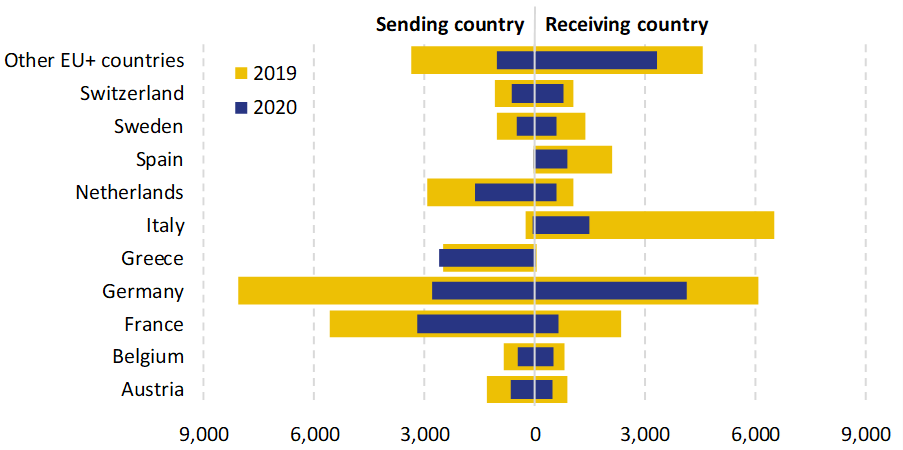

Four countries – France, Germany, Greece and the Netherlands – implemented over three-quarters of all transfers in 2020. They were also the main countries in 2019 to implement transfers albeit in a different order. All but one Member State implemented fewer transfers in 2020 (see the left side of Figure 4.9). Greece stood out as an exception, carrying out 4% more transfers in 2020 than in 2019, the majority of which were in the context of the relocation scheme for unaccompanied minors and vulnerable families (under Article 17(2)). The largest absolute decreases in transfers were reported for Germany and France (in descending order).

The situation was similar for countries receiving transfers. Almost all Member States received fewer transfers than in 2019 (see the right side of Figure 4.9), except for the UK (+4%).xxv The rise in the UK may be related to Brexit, with countries (primarily Greece and France) seeking to transfer as many people as possible before the Dublin III Regulation no longer applies to the UK.

In order to facilitate the implementation of Dublin transfers, new administrative arrangements between Germany and the Netherlands came into force on 10 January 2020, introducing updated notice periods for transfers: 14 days for collective transfers, with the final list of names to be submitted 10 days before the transfer; 3 days to transfer an individual applicant; and 10 days for vulnerable applicants.375

Some transfers could not be implemented within the time limit during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the State Secretary for Justice and Security in the Netherlands noted that approximately 1,500 cases were added to the national case load because Dublin transfers could not be implemented. The pandemic was one of the factors, in addition to the more general issue of applicants who abscond. Many of the Dublin cases in the Netherlands had already been delayed by the time they became part of the national stock.376

| Fewer transfers implemented by almost all Member States except for Greece |

Source: EASO.

Most of the transferees in 2020 were nationals of Afghanistan, accounting for 17% of all persons who were transferred. This nationality was followed at some distance by Iraqis (7%), Nigerians (6%), Algerians and Syrians (5% each). Transfers involving these nationalities decreased when compared to 2019. However, the number of Afghan transferees decreased only slightly (- 6%), and in fact, a sharp increase in Afghan transfers was reported in the last months of 2020 (see Figure 4.8). It is noteworthy that Greece executed many more transfers of Afghans in 2020 than in 2019 (linked to relocations under Article 17(2)), particularly to France, Germany and Switzerland.

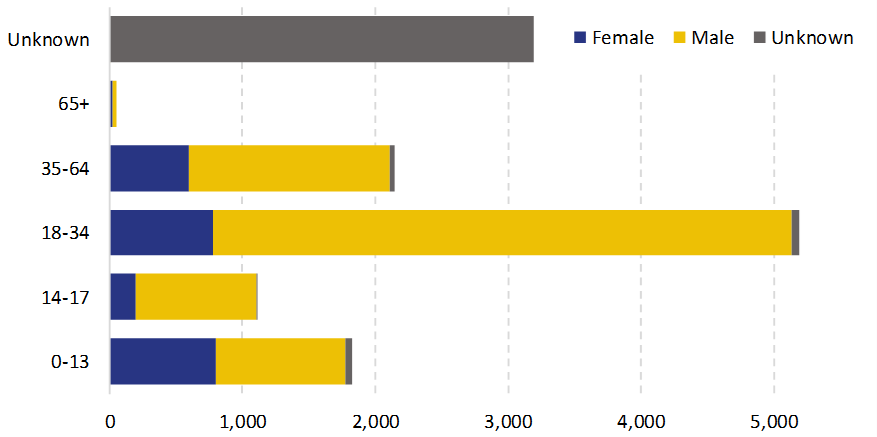

Men over the age of 18 accounted for the majority of transferees (see Figure 4.10). While the age group was not reported in 24% of transfers, minors represented at least 22% of all transferees in 2020. Although the overall number of minors who were transferred was lower than in 2019, their share of all transferees increased in 2020. Over four-fifths of minors over 14 years of age who were transferred between EU+ countries were male. In contrast, for minors younger than

14 years, the sex ratio was more balanced. Only in transfers carried out by Greece, minors accounted for the majority of transferees, largely linked to relocations.xxvii

Most of the minors who were transferred in 2020 were Afghans. This was followed at quite some distance by Syrians, Iraqis, Russians, Pakistanis and Turks (in descending order). Transfers of Afghan minors rose considerably compared to 2019, particularly from Greece to France, Germany and Switzerland.

| Most transferees were men aged 18-34 years |

Figure 4.10: Transferees in Dublin procedures by age group and sex, 2020

Source: EASO.

National courts received many appeals related to transfer modalities and time limits. Many of these appeals related to the calculation of transfer time limits in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, several applicants contested that BAMF in Germany made an ex officio decision to suspend the execution of Dublin transfers based on Dublin III Regulation, Article 27(4). It argued that this article allows for such a suspension – and the interruption of the transfer period, as a consequence – even without a pending appeal or review. Regional courts delivered diverging decisions on this issue. For example, in the case of an Afghan applicant’s transfer to Greece, the regional administrative court noted that the suspension based on this article must serve to enable effective legal protection and this was not the objective of the BAMF decision. Thus, the suspension was against the law and annulled the inadmissibility decision that the applicant received. The regional administrative court reached a similar conclusion in the case of a Nigerian applicant’s transfer to Italy.

Other regional administrative courts reasoned to the contrary and the case of an Iraqi national’s transfer to Austria was seen as lawful. This was also the case for an Irani applicant’s transfer to Poland and another Irani applicant’s transfer to Poland. However, higher administrative courts, in line with the European Commission’s guidance, underlined that BAMF’s suspension decision under national law cannot suspend the transfer period under the Dublin III Regulation, for example in a case decided in Lower Saxony and in another case from Schleswig-Holstein.

The Dutch State Secretary for Justice and Security reasoned in April 2020 that the court’s decisions on the expiry of transfer time limits should be adjourned, pending further guidance from the legal service of the JHA Council. However, the court underlined that the European Commission’s guidance was clear that the transfer time limits should not be extended due to the pandemic and there was no evidence on the possibility that new guidance would emerge, which would retroactively change the applicable provisions of the Dublin III Regulation. The court delivered similar judgments in the case of a Sudanese applicant’s transfer to France.

Courts in Belgium and France interpreted the notion of absconding and the subsequent prolongation of the transfer period. The Belgian CALL based its judgment on the CJEU decision in Jawo and noted that the mere fact that the applicants did not return the declaration on voluntary return within the legal deadline cannot automatically be interpreted as a sign that the applicants wanted to abscond and prevent the transfer. Thus, it cannot automatically lead to a decision on the prolongation of the transfer period. The French Council of State noted that an applicant can be considered as absconded when they were informed clearly and in a language they understand about the exact arrangements of the transfer and they deliberately did not comply with the authority’s directives for the transfer. However, the mere fact that the applicant did not arrive on time at the planned place of departure cannot automatically lead to a decision that he or she has absconded.

The Dutch Court of the Hague ruled that the Netherlands became responsible to examine an asylum application 18 months after Italy first accepted responsibility and the chain rule – that was applicable under the Dublin II Regulation and which interrupted the transfer time limit – does not apply under the Dublin III Regulation, Article 29. In this case, the applicant absconded after the Italian authorities accepted responsibility and submitted an application first in Switzerland, then again in Italy, before returning to the Netherlands and submitting a new asylum application after the expiry of the initial transfer time limit. The national authorities foresaw to further assess the implications of the court ruling.

The Supreme Administrative Courts in Lithuania and Czechia assessed the legality of an applicant’s detention in the framework of the Dublin procedure (see Section 4.8).

[xxiii] Data were not available for Cyprus and partially missing for Denmark.

[xxiiv] The ratio of transfers following accepted requests should be used with caution to assess a Member State’s capability to successfully implement transfers due to the lack of cohort data and given that there might be a substantial time lapse between an accepted transfer request and a physical transfer. This time lapse distorts the calculation of the rates if the number of acceptances is not stable over time.

[xxv]Only countries implementing at least 50 transfers in 2020 are considered.

[xxvii] Only countries implementing at least 50 transfers in 2020 are considered.

_____________

[375] Repatriation and Departure Service | Dienst Terugkeer en Vertrek. (2020, February 14). Overeenkomst tussen Duitsland en Nederland over Dublin-overdrachten [Agreement between Germany and the Netherlands on Dublin transfers]. https://www.dienstterugkeerenvertrek.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/02/14/overeenkomst-tussen-duitsland-en-nederland-over-dublin-overdrachten

[376] Ministry of Justice and Security | Ministerie van Justitie en Veiligheid. (2021, January 7). Kamerbrief over voortgang afdoen vertraagde zaken IND [Parliamentary brief on the progress of treating the backlog cases of IND]. https://ind.nl/Documents/TK%20Voortgang%20afdoen%20vertraagde%20zaken%20IND.pdf