Events such as conflict, economic hardship, deteriorating governance, political tensions and social exclusion of marginalised groups have the potential to internally displace entire communities or force them to leave their homes to seek refuge in other countries. EASO uses big data on global media reports168 to quantify the frequency of such events, which are selected and weighted according to the magnitude of the effect they are likely to have on asylum-related migration. In the interests of simplification and to enable further analyses, these data have been aggregated into a composite indicator for each country of the world, referred to as the Push Factor Index (PFI).

The PFI correlates with administrative indices, such as the number of asylum applications lodged by citizens of a specific country. Due to the complexity of asylum-related migration, no single indicator can entirely explain or predict patterns. However, the PFI, which can be updated on a daily basis, provides an estimation of the root causes of asylum-related migration and delivers a robust framework for predictive analyses.

Figure 4.5 shows that the PFI correlates with the number of asylum applications lodged in EU+ countries. In fact, 29 % of the variation (R2) in applications lodged is explained by between-country differences in push factors, with a correlation coefficient of 0.54 for all countries that have PFI greater than 0. The relationship between the PFI and applications is strong and clear for countries placed along the trend line (for example, Bangladesh and Somalia), but the placement of each country in the analytical space also raises thought-provoking questions and adds information to better understand migratory patterns.

Countries placed above the line lodged more applications than expected based on push factors. Potential explanations include repeat applications in the same year but also pull factors generated by family members already living in Europe. A trend in 2019 showed that many visa-free countries lodged more applications than push factors would predict, possibly related to the enabling factor of visa-free travel. For example, Albania and Georgia have very low Push Factor Indices but lodged a high number of applications, possibly because nationals from these countries can enter the EU without a visa169 and so may not be fleeing in response to specific push factors. In countries like Eritrea, push factors may exist that are not reported in the media due to low press freedom.170

Conversely, countries placed below the trend line lodged fewer applications for asylum than expected based on their push factors. Some of these, such as China, India, Palestine, Russia, Sudan and Ukraine had high push factors but a low number of applications which could be explained in several ways, including barriers to migration, internal displacements or seeking refuge in neighbouring countries rather than in EU+ countries.

Figure 4.5 Correlation between the Push Factor Index and number of applications for international protection in EU+ countries, Top 30 countries of citizenship of applicants, 2019

Note: Data are log transformed to reduce the skew and induce symmetry.

Sources: Administrative data from Eurostat for applications for international protection. EASO for the Push Factor Index.

Overall, in 2019 the correlation was lower than in previous years, especially for African countries of origin. This can be explained by the closure of the Central Mediterranean route in mid-2018171 and an increase in patrolling by Libyan coast guards. In other words, although push factors remained high in many countries, migration flows were reduced due to common routes being closed or monitored.

Intensity and change of push factors

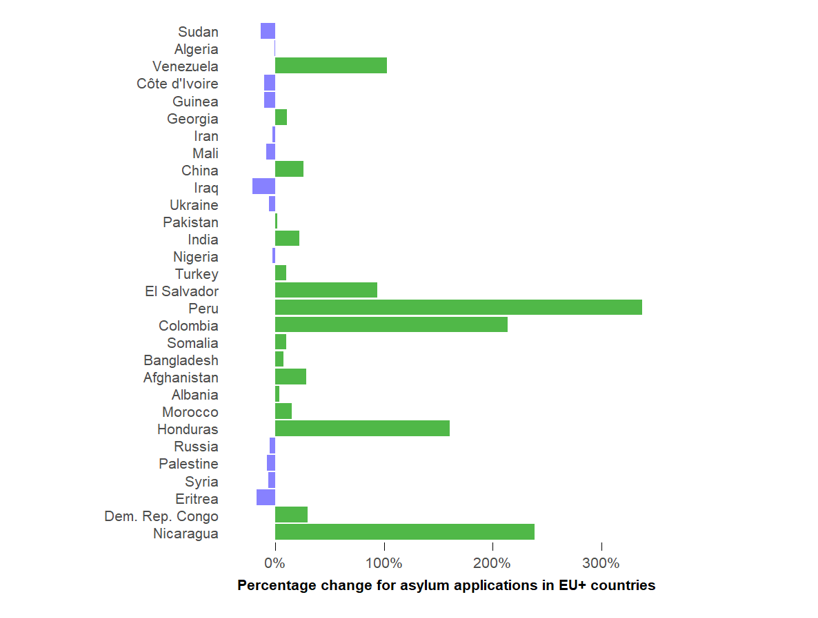

Figure 4.6 presents the Top 30 countries of origin for applicants, indicating where push factors increased or decreased. In many cases, changes in the PFI were closely related to similar changes in the number of applications lodged (see Figure 4.7). For instance, push factors increased in Venezuela by 50 % and in Georgia by 15 %, while citizens from these countries also lodged more applications for asylum in EU+ countries: Venezuelans with 103 % more applications in 2019 and Georgians with 11 % more. Similarly, the PFI fell in Nigeria by 6 % and Eritrea by 34 %, while citizens from these countries lodged fewer applications overall in Europe: applications by Nigerians fell by 2 % in 2019 and by Eritreans by 17 %. Likewise, Syrian nationals lodged 6 % fewer applications for asylum following a decrease in push factors of 27 %.

Nonetheless, changes in the PFI were not always related to the number of applications lodged. For example, the PFI decreased in Afghanistan and Turkey, by 19 % and 11 % respectively, but applications by nationals of these countries increased by 28 % and 10 %, respectively, in 2019. The opposite was true for Iran and Iraq, where push factors increased by 13 % and 9 % respectively, while asylum applications by their nationals fell by 3 % and 19 % respectively.

Such discrepancies may be the result of a multitude of factors which are not captured by this approach. Explanations include the delay between the development of push factors in countries of origin and the arrival of migrants in EU+ countries, additional push factors not reported by media, alternative migration destinations and barriers to migration.

Figure 4.6 Annual percentage change for the Push Factor Index in EU+ countries, Top 30 citizenship of applicants, 2018-2019

Figure 4.7 Annual percentage change in the number of applications for international protection in EU+ countries, Top 30 citizenship of applicants, 2018-2019

Source: Eurostat.

Figure 4.8 World map of the Push Factor Index, 2019

Source: EASO.

_____

168 Data on events are extracted from the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (Gdelt), https://www.gdeltproject.org/

169 Nationals of Georgia can enter the EU visa-free since 2017, while Albanian nationals can do so since 2010. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/international-affairs/eastern-partnership/visa-liberalisation-moldova-ukraine-and-georgia_en, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_10_621

170 Eritrea ranks 178th in the 2019 World Press Freedom Index, https://rsf.org/en/eritrea

171 Frontex FRAN Q2 2018, https://frontex.europa.eu/publications/fran-q2-2018-EkjTNR

Previous |

............... |

Home |

................... |

|

Next |