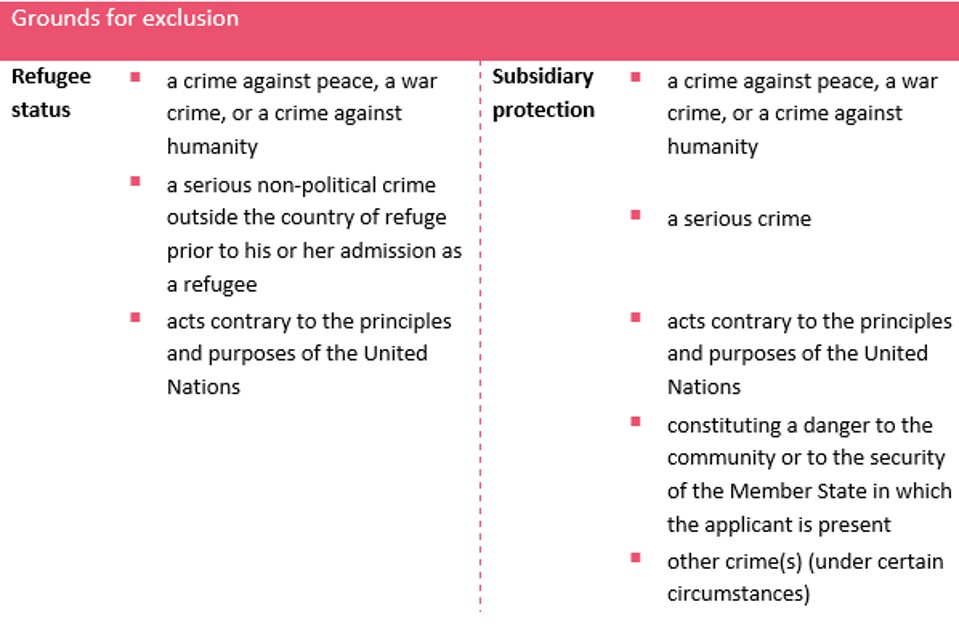

Article 12(2)(a) QD and Article 17(1)(a) QD refer to specific serious violations of international law, as defined in the relevant international instruments.[7]

It can be noted that the ground ‘crime against peace’ would rarely arise in asylum cases. However, it may be of relevance with regard to high-ranking officials responsible for the invasion of Kuwait.

Violations of international humanitarian law by different parties in the current and in past conflicts in Iraq could amount to war crimes, such as the use of prohibited weapons and the deliberate indiscriminate attacks on civilians, etc.

Reported crimes such as murder, torture, and rape by the different actors could amount to crimes against humanity when committed as part of a widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population. Crimes in the context of past events, such as the Al-Anfal military campaign could also trigger the consideration of exclusion in relation to ‘crimes against humanity’.

Some acts in the current conflicts, such as extrajudicial killings, torture, forced disappearance, could amount to both war crimes and crimes against humanity.

According to COI, especially (former) members of insurgent groups (e.g. ISIL), security actors (e.g. ISF, PMF), as well as Baathists, can be implicated in acts that would qualify as war crimes and/or crimes against humanity. Relevant situations, which should be considered in relation to this exclusion ground include, for example:

- Iraq - Iran war (1980 - 1988): international armed conflict;

- Al-Anfal military campaign (1987 - 1988);

- Invasion of Kuwait (1990 - 1991): international armed conflict; and subsequent uprising;

- Kurdish civil war (1995 - 1998): non-international armed conflict;

- Invasion of Iraq (2003): international armed conflict;

- Armed conflict between ISF and insurgent groups as from 2004: non-international armed conflict;

- Sectarian conflict/civil war (post 2003): non-international armed conflict;

- ISIL conflict (2014 - ongoing): non-international armed conflict;

- Turkey - Iraq conflict (2019 - ongoing): international armed conflict.

[7] The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court is a particularly relevant instrument in this regard. See also the ‘Grave Breaches’ provisions of the 1949 Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I, common Article 3 and relevant provisions of Additional Protocol II, the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR).

In the context of Iraq, widespread criminality makes the exclusion ground ‘serious (non-political) crime’ particularly relevant. This is related to criminal activities of organised groups and gangs, as well as activities of ISIL and some militia, but the ground also applies to serious crimes committed by individuals not related to such groups.

Some particularly relevant examples of serious (non-political) crimes include kidnapping, extortion, trafficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation, etc. For example, criminal gangs in Basrah have exploited the security gap and there has been a rise in robberies, kidnapping, murder, and drug trafficking.

Violence against women and children (for example, in relation to FGM, domestic violence, honour-based violence, forced and child marriage) could also potentially amount to a serious (non-political) crime.

Some serious (non-political) crimes could be linked to an armed conflict (e.g. if they are committed in order to finance the activities of armed groups) or could amount to fundamentally inhumane acts committed as a part of a systematic or widespread attack against a civilian population, in which case they should instead be examined under Article 12(2)(a)/Article 17(1)(a) QD.

(Former) membership in terrorist groups such as ISIL and Al-Qaeda could trigger relevant considerations and require an examination of the applicant’s activities under Article 12(2)(c) QD/Article 17(1)(c) QD, in addition to the considerations under Article 12(2)(a) QD/Article 17(1)(a) QD, mentioned in the sections above.

The application of exclusion should be based on an individual assessment of the specific facts in the context of the applicant’s activities within that organisation. The position of the applicant within the organisation would constitute a relevant consideration and a high-ranking position could justify a (rebuttable) presumption of individual responsibility. Nevertheless, it remains necessary to examine all relevant circumstances before an exclusion decision can be made.

Where the available information indicates possible involvement in crimes against peace, war crimes or crimes against humanity, the assessment would need to be made in light of the exclusion grounds under Article 12(2)(a)/Article 17(1)(a) QD.

In the examination of the application for international protection, the exclusion ground under Article 17(1)(d) QD is only applicable to persons otherwise eligible for subsidiary protection.

Unlike the other exclusion grounds, the application of this provision is based on a forward-looking assessment of risk. Nevertheless, the examination takes into account the past and/or current activities of the applicant, such as association with certain groups considered to represent a danger to the security of the Member States or criminal activities of the applicant.