COMMON ANALYSIS

Last updated: June 2022

The structure of the Somali governance

COMMON ANALYSIS

Last updated: June 2022

Somalia is a Federal State composed of two levels of government: the federal government and the FMS, which include both state and local governments. FMS also dispose their own constitutions and armed forces.

As of August 2021, the country was to complete a long-delayed parliamentary and presidential election between July and October 2021. Ever since, the country has been experiencing a strongly polarised electoral and political impasse. The incumbent president of the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, also known as Farmaajo, term’s extension was met with political unrest, international criticism, and street protests, which also broke out in armed fighting in downtown Mogadishu. [Security 2021, 1.1; Actors, 2]

Somalia is de-facto ruled by a gentlemen agreement among the major clan-families that dominate the country. Based on this agreement, also known as the 4.5 power-sharing formula, key positions in the State apparatus, including parliamentary seats, are (more or less) proportionally distributed among the four main clan families as well as the 0.5 quota representing minorities. [Actors, 2.1]

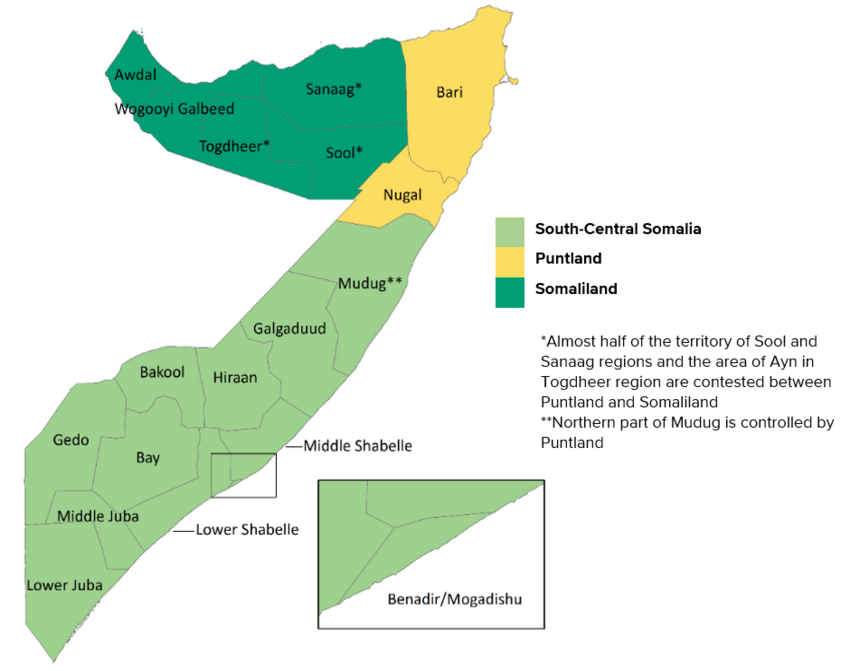

South-Central Somalia includes the following FMS: Jubbaland, South-West, Benadir, Hirshabelle and Galmudug. Mudug region is divided between Galmudug and Puntland, with Galmudug controlling the southern half of the region [Security 2021, 2.5.2.1].

Puntland, as a self-proclaimed autonomous state within the Somali Federal State, was established on 1 August 1998 as an entity representing clans belonging to the Harti clan collective. Puntland has developed significant institution-building and governance mechanisms. However, it continues to be affected by security, humanitarian, political, and socio-economic challenges. [Actors, 7.6]

Somaliland declared its independence in 1991 while the civil war was occurring in the rest of Somalia. The backbone of Somaliland’s administration was drawn from the Somali National Movement (SNM), comprising several Isaaq clans [Actors, 3.4.2]. Ever since, Somaliland has embarked on an institution-building and democratisation process, combining, in a hybrid entity, traditional and modern forms of governance that make it stand out compared to other parts of Somalia [Actors, 7.7]. Somaliland remains largely internationally unrecognised, despite a recent increase in the number of states with which it holds diplomatic relations [Actors, 7.7.1; Socio-economic 2021, 3].

In terms of territorial control and influence, areas of Sool and Sanaag regions and the area of Ayn (Togdheer region) are contested between Somaliland and Puntland [Security 2021, 2.6.3, 2.6.4].

The following map indicates roughly the macro-zones of Somalia (South-Central Somalia, Somaliland, Puntland), as described above. This illustration intends to provide to the user of the present guidance a general depiction of these areas on the map. Please note that for specific and more clear information regarding the territorial control of different actors in Somalia and/or the contested territories, see chapter Actors of persecution or serious harm and the map (Figure 10), included in that section.

Figure 9. Macro-zones of Somalia.

This country guidance is based on an assessment of the general situation in the country of origin. Where not specified otherwise, the analysis and guidance refer to Somalia in general, including Puntland and Somaliland. In some sections, the COI summary and respective analysis specify the particular area(s) they refer to.

The individual assessment of international protection needs should take into account the presence and activity of different actors in the applicant’s home area and the situation in the areas the applicant would need to travel through in order to reach their home area.

The role of clans in Somalia

COMMON ANALYSIS

Last updated: June 2022

Layered in all aspects of life, the clan is both a tool for identification and a way of life. Clans define the relationship between people and all actors in Somalia, including Al-Shabaab, must deal with the clan variable [Actors, 3, 3.1]. Belonging to a strong clan matters in terms of access to resources, political influence, justice, and security [Targeting, 4].

Somalis are roughly divided in five large family clans: the Dir are mainly present in the western part of Somaliland and in the southern part of Somalia; the Isaaq are mainly present in the middle part of Somaliland; the Darood are mainly settled in Puntland, in the eastern part of Somaliland and in the southernmost part of Somalia; the Hawiye are mainly present in central Somalia; the Rahanweyn, sometimes called the Digil-Mirifle group, are mainly present between the Jubba and the Shabelle rivers [Actors, Clan maps, 3.1.1]. Even though this clan-territory association remains relevant, sometimes it must be relativised, notably in urban contexts (e.g. Mogadishu, Garowe) [Actors, 3.1.1; Socio-economic 2021, 1.1.1, 2.1.1].

Dominant clans have so far maintained an ‘artificial’ balance in terms of political power in the Federal State of Somalia, with the presidency and premiership alternating between the Hawiye and the Darood, the speakership of the parliament assigned to the Rahanweyn, and the supreme court to the Dir. The FMS’ administrations function, in general, with clearer clan affiliation, with all main power functions gathered in the hands of the locally dominant clans. [Actors, 1, 2.1]

Large segments of the Somali population are considered as minorities, either in local context or in Somalia in general, living amongst larger clans. For more information on some minorities and their treatment, see profile 2.9 Minorities.

Somalis are traditionally attached to a territory where their kin are supposed to be more numerous [Actors, 3.2.1]. Until today, most Somalis still rely on support from patrilineal clan relatives [Targeting, 4].

The most important level of solidarity in Somali society, the jilib, does not refer to a particular number of individuals or a level in the genealogical tree but rather to the group below which the community assumes the payment of ‘the blood price’ (diya). In theory, inside the jilib, the community must help individuals in case of smaller or larger problems, reaching as far as the mutilation or the murder of someone from another clan (blood price). [Actors, 3.2.1]

Arrangements can also be made between clans for protection outside the clan. These agreements are often for a precise duration and specify the kind of protection, the means of resolution of conflicts, marriage rules, etc. There are also binds of protection and solidarity without duration or a specific agreement. In the Somali perception, there are several levels of clan protection corresponding to different scales of social closeness, each of these levels coming with a given intensity of protection. Military alliances can also be made between clans. A gaashaanbuur (military alliance) integrates one or several clans or parts of these to wage war. [Actors, 3.2.2]

Clans often compete against each other, as well as against other actors, such the FGS or the FMS, for political, resource and territorial control, while resorting to a system of instrumental alliances [Actors, 1]. Clan militias are also important actors of political life across Somalia (for more information, see section 1.4 Clans and clan militias under chapter Actors of persecution or serious harm [Actors, 3.4].

Under the xeer system, clan elders act as mediators or arbiters, and play a central role in the resolution of local and intra-clan disputes [Actors, 2.3.2]. For more information on the different justice systems in Somalia, see chapter Actors of protection.